Lieutenant

Lieutenant William Maitland-Dougall, RCN: probably taken when he was CO of D3. Maitland-Dougall family collection.

One morning in early January 1911, a British Columbia teenager packed his bags and bade his parents and younger brother a wrenching goodbye. He was leaving for Halifax to join the first term of cadets at the new Royal Navy College of Canada. William Maitland-Dougall at 15 was a good candidate – intelligent, energetic, and self-confident.

Two years later, Willie graduated with honours and went to sea in the gunroom of a British cruiser. World War I broke out while he was pursuing further studies at RNCC and the fledgling Royal Canadian Navy posted him to Esquimalt in August 1914 as one of two midshipmen for new Canadian submarines. The young man was disappointed, but his cheerful optimism soon had him hoping his turn on a battleship would come.

The acquisition of the two submarines was a surprise to the RCN. The premier of British Columbia, Sir Richard McBride, purchased them secretly without approval from Ottawa as the Great War dawned, having heard that German cruisers might threaten Victoria. A few days later, the Dominion government reimbursed the province and transferred the boats to the RCN.

Willie Maitland-Dougall in happier days, with fellow members of the Royal Naval College of Canada Rowing Team, during a race against HMS Cornwall, May 1912. (The RNCC team won by five lengths). Maitland-Dougall is pictured on the left-hand side of the boat, front of row, seated. CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum collection, VR 992.141.1.

Maitland-Dougall, now tall and outgoing, joined a motley crew for a crash course in submarines. The officers were mainly retired RN types and reservists, and the ratings were raw recruits from the streets of Victoria, leavened with a handful of experienced surface sailors. Together, they crawled around the submarines studying their complex systems and practised the unfamiliar routines, first alongside and then at sea, under the expert eye of a pioneer RN submariner.

Still unnamed and unarmed, the boats made short patrols in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Without torpedoes, it was fortunate the German cruisers failed to appear. Maitland-Dougall stood watches, both on the surface and submerged using the periscope, and began to appreciate the sub-surface life despite its hardships. In October the RCN christened the boats CC1 and CC2 – the first C for Canada and the second C for a similar class of boat in the RN.

Once the threat subsided, the tempo of operations slackened to a care and maintenance routine and Maitland-Dougall moved on. He didn’t get the battleship he wanted and thought that submarines might be his best option – they offered excitement, rapid promotion, and a chance of early command. May 1915 saw him officially volunteer for submarines and request a transfer to the RN.

Willie Maitland-Dougall (standing) with his brother, Hamish, who was on embarkation leave for Vimy, 1917. Maitland-Dougall family collection.

Within the month, Maitland-Dougall’s submarine career was on fast-forward. He sailed in H10 across the Atlantic to Portsmouth; aced the basic submarine course there, and rejoined H10 for patrols in the North Sea. Next came a stretch as First Lieutenant in D3, whose CO was LCdr. “Barney” Johnson, RNR, from CC2. They made a good team in the Western Approaches, claiming one U-boat sunk and another damaged. During this posting, Maitland-Dougall became an Acting Lieutenant and learned his younger brother, Hamish, had been killed at Vimy.

By now, the RN had earmarked the young submariner for command. He said goodbye to Johnson and entered the newly established Periscope School at Portsmouth. After passing the course that taught the art of submerged attack, Maitland-Dougall returned to D3 as her captain. He inherited a happy and efficient crew that he knew well, and they began patrolling in the English Channel under the watchful eye of their flotilla commander, Cdr. Alex Quicke, his former Commanding Officer from H10. These patrols were shorter, but more hectic. The heavy shipping in restricted waters complicated matters, and D3 was frequently attacked by her own side.

On March 7, 1918, Lt. Maitland-Dougall, RCN, took D3 to patrol off Le Havre, France. He was in high spirits – it would be a short patrol and he would be ashore in time to celebrate his 23 rd birthday. But D3 did not return.

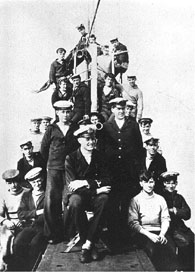

SLt. Maitland-Dougall (front-centre), First Lieutenant of D3, with the crew during operations in the Western Approaches, 1917. RN Submarine Museum image 3027.

What happened was not revealed to the grieving relatives of the crew until several years later. Bombs dropped by a French airship on March 12 sank D3 – the French had not known the Allied submarine recognition signals. Maitland-Dougall and his crew fought to save her but she was lost with all hands. (British divers located the wreck of D3 in 2007.)

The Royal Canadian Navy has never officially recognized the accomplishments of Lt. Maitland-Dougall, RCN, then or now. Indeed, few modern submariners have even heard his name. Maitland-Dougall was the first and only Canadian submarine commanding officer to be lost in action. He also remains the youngest to earn command.

Coming less than a year after Hamish was killed, the loss of Willie was devastating to his parents. His mother Winifred never fully recovered from the news. She took some comfort in designing a memorial to her sons and, in 1921, she placed a plaque in the parish church where her boys had been baptized and confirmed. Today visitors can see it over the pew the Maitland-Dougall family always used in St. Peter’s Anglican Church, Quamichan, on Vancouver Island.

This article is copyrighted

© Julie H. Ferguson 2015

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum