Hollywood’s lights have sometimes shone down brightly on the ships – and sailors – of Canada’s navy.

However, naval vessels and personnel haven’t always received the kind of recognition or billing they deserved from Tinseltown.

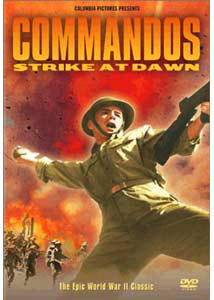

In 1942, for example, the film shoot for Columbia Pictures’ Commandos Strike at Dawn made extensive but largely uncredited use of HMCS PRINCE DAVID. The movie was made in and around the Saanich peninsula on southern Vancouver Island, which stood in for Norway in this rousing wartime morale raiser.

During the production, Commandos’ director John Farrow, father of actress Mia Farrow, attracted extraordinary cooperation from Canada’s forces. This included the assistance of PRINCE DAVID, then on leave from searching for Japanese troops and activity in the Aleutian islands, plus planes, pilots and troops. Given that this was wartime, the level of assistance was unusual even by Hollywood standards.

It was possibly because Farrow was a navy man himself that he received the red carpet treatment. He was an Honorary Commander in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR), an almost unheard of distinction, and was later made a Commander of the British Empire (CBE).

Canadian sailors pose with John Wayne (centre, front row), star of The Sea Chase, during a tour of Universal Studios. Photo courtesy of Lynn Bergman, whose father Leading Seaman Gilbert Louis Lucier is 2nd row from the back, last man on the right.

In the mid-1950s, HMCS NEW GLASGOW, substituting for HMAS Rockhampton, was involved in another film directed by Farrow, The Sea Chase. The movie starred John Wayne as captain of a run-down German freighter under pursuit in Australian waters.

The Great Impostor starred Tony Curtis as Ferdinand “Waldo” Demara, an American who joined the Royal Canadian Navy and successfully passed himself off as a medical doctor aboard HMCS CAYUGA during the Korean War. For the movie, HMCS ATHABASKAN stood in for CAYUGA. A Prestonian Class frigate, HMCS STE. THERESE, was also used for scenes depicting CAYUGA’s interior. Like most movies of its kind, The Great Impostor was full of inaccuracies when it came to sailors and shipboard life in the navy.

By far the best of an often mediocre lot when it comes to films portraying the action, adventure and real-life drama of sailors in wartime was Corvette K225. The film, made in 1943, stars Randolph Scott, who turned in a strong performance. But the movie also drew strength from real action footage of actual WWII convoys during the Battle of the Atlantic, which the Royal Canadian Navy is often credited with winning in cooperation with the Merchant Navies.

Some consider HMCS KITCHENER, the genuine 225, to be the real star of the show. In their book The Ships of Canada’s Naval Forces 1910-2002, by Ken Macpherson and Ron Barrie, the authors note that KITCHENER carried out workups at Pictou, Nova Scotia before briefly joining the convoy escort force in September 1942. “It may have been during this unusually long workup that she starred in the film Corvette K225,” they point out. But it was another Canadian naval vessel, HMCS KAMLOOPS, that was used for most of the shots.

In the movie K-19 The Widowmaker starring Harrison Ford, there is a Canadian warship (possibly HMCS TERRA NOVA) posing as a U.S. Destroyer. And director Michael Bay’s 2001 film Pearl Harbour includes footage of HMCS REGINA and HMCS PROTECTEUR, and may also show HMCS ALGONQUIN. They were captured on film during the world’s largest international maritime exercise, RIMPAC, hosted and administered biennially by the Royal Navy and United States Navy.

More recently, the 1993 made-for-t.v. production Lifeline to Victory showcased HMCS SACKVILLE, the last surviving example of the more than 120 corvettes built in Canada during WWII. SACKVILLE is now operated as a floating museum and memorial by the Canadian Naval Memorial Trust.

All the scenes in the film where someone was seen throwing up were reportedly genuine; after a day of filming in and around Halifax harbour, everyone, cast and crew alike, became seasick. Which just goes to show that even Hollywood types are susceptible to the forces of nature.

By Clare Sharpe

Museum staff member/webmaster

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum