Winged horses, dragon-like monsters, birds and beasts — all of these creatures, real and mythical, feature in the official badges of Canada’s Navy.

The practice of displaying badges is probably as old as warfare itself.

Detail from the badge of HMCS GRIFFON, showing a mythical creature with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion.

In combat at sea and on land, a distinctive emblem helped to identify friend or foe. In the Middle Ages, warriors on the battlefield carried specially designed shields to show at a glance which side they were fighting on. It was during this period that such emblems flourished, and the system of signs and symbols known as heraldry (still in use today) reached its height.

Besides the obvious importance of telling allies from enemies in naval warfare, badges also evolved into symbolic representations of individual vessels, reflecting the distinctive character of particular ships, or the Canadian communities they are connected with.

In Canada, ships are often named for cities, towns and provinces. Their badges tend to feature animals – national icons like the beaver, bear, and moose – that have become part of Canada’s identity.

Also popular are elements of the landscape such as rivers and trees, wheat sheaves and bullrushes.

The aboriginal people of Canada and their imagery are a recurring badge motif. For their power, these images draw on the strength, endurance and success in battle often associated with First Nations peoples.

The badge of HMCS HAIDA, for example, takes as its inspiration and source the thunderbird legend. The thunderbird is a creature featured in certain North American indigenous peoples’ history and culture. It is considered a supernatural bird of power and strength. It is especially important, and frequently depicted, in the art, songs and oral histories of many Pacific Northwest Coast cultures.

The singular thunderbird (as the Nuu-chah-nulth thought of it) was said to reside on the top of a mountain, and was the servant of the Great Spirit. It was also told that the thunderbird controlled rainfall. The plural thunderbirds (as the Kwakwaka’wakw and Cowichan tribes believed) could change into human form by tilting back their beaks like a mask, and removing their feathers as if it were a feather-covered blanket.

In the case of HMCS HAIDA, the thunderbird, believed to make thunder with the flapping of its wings, is likened to the thundering sound of HAIDA’s guns, and her power to scare off enemy ships.

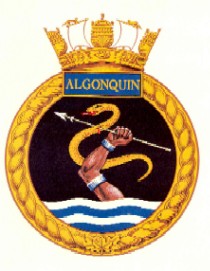

Retired naval Commander Latham Jenson, who designed the badge for HMCS ALGONQUIN, acknowledges his debt to First Nations sources in the following account of the badge’s genesis:

Algonquin’s name had been Valentine before she was turned over to the Canadians, and Valentine’s ship badge would be easy to visualize.

Algonquin was not as simple. I went to the library to learn about the tribe for whom we were named. Algonquins lived in Ontario and Quebec, and the name in their tongue indicated “the place of spearing fish and eels.” I made a drawing of an arm holding a spear over heraldic waves. Impaled on the spear writhed an eel, which was meant to represent an evil German submarine.

I showed my drawing to the captain. His reaction was to show the arm coming up out of the water bent, exactly like the arm on the Royal Military College of Canada’s badge.

I adjusted my drawing and we passed the design on to John Brown’s, our builder . . . .

The above quote is taken from Latham Jenson’s book Tin Hats, Oilskins & Seaboots, published by Robin Brass Studio Inc., Toronto.

by Clare Sharpe

Museum staff member/webmaster

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum