Unknown Inventor

Horace Carley was born July 22, 1838 in Sherborn, Massachusetts, and fought in the American Civil War in his youth, enlisting as a private in Company K in the 30th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

His invention saved countless sailors from death in cold and perilous waters.

His name is still synonymous with the life-raft he designed and created.

However Horace Carley the man is largely forgotten. Without Carley’s ingenuity, untold thousands of sailors might have perished at sea. His invention changed maritime rescue practices and was a boon to mariners worldwide.

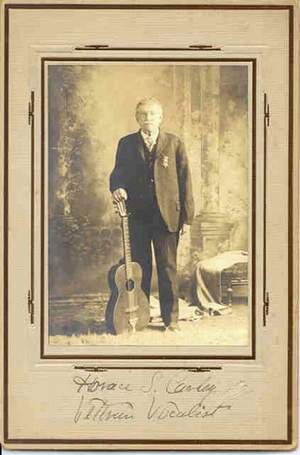

Yet Horace Carley did not test and market his design for a sturdy, self-righting life-raft until he was well into his sixties. By then he had already had a full and varied career as a soldier, inventor, artist and musician, to name just a few of his many talents.

He was born July 22, 1838 in Sherborn, Massachusetts, and fought in the American Civil War in his youth, enlisting as a private in Company K in the 30th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. He was honourably discharged at New Orleans in 1862 due to disability. Less than a year later, Carley re-enlisted for service in an armed schooner, the Thomas Woodard. The Woodard‘s mission was to seek and destroy the Confederate steamer Tacony, which was busy attacking and sinking Gloucester’s fishing fleet. It was a mission that proved unsuccessful.

In civilian life, his pursuits were varied. By profession he was an interior decorator, but being gifted with musical talent, he also enjoyed singing and playing. For some years he was associated with travelling minstrel shows, in which he played starring roles.

It is possible that the idea for the float may have been with Horace Carley for decades. At age 16, he worked aboard a whaling ship, hunting for whales in Hawaiian waters. He witnessed his share of tragedies at sea, as would virtually any sailor of the period. But it was a pair of notable nautical disasters at the close of the 19th century that prompted Horace Carley to move his design off the drawing board and into production.

His life-raft had already been under development for years when, in July 1898, the French steamer La Bourgogne was in collision with a British sailing vessel off Cape Sable, Nova Scotia in deep fog; 571 lives were lost. In November the same year, the American steamer Portland was wrecked off Cape Cod, Massachusetts; 157 lives were lost.

In the La Bourgogne collision, the passengers panicked and there was a dash for the boats and much bad behaviour as people struggled to survive. The ship was also not equipped to cope with such a scenario. The only boats fit for service were on the port side (the collision smashed all those to starboard), and no lifebelts were distributed. Those who couldn’t swim drowned immediately they fell into the water.

The Portland, a 19th-century steamship, sank in one of worst hurricanes in New England’s history, a disaster that prompted changes in ship design and maritime practices.

She went down off the Massachusetts coast on Nov. 26, 1898. More than 190 people died. The vessel had ignored storm forecasts and sailed from Boston bound for Portland, Maine. Tragically, she was caught up in the “Portland Gale“, the 19th century equivalent of the “Perfect Storm“. Bodies and wreckage began to wash up on the shores of Cape Cod soon after the storm, and Portland came to be known as the “Titanic of New England“.

Horace Carley’s float was an important innovation because it launched with comparative speed and ease. It was light enough to be launched quickly and without special machinery or davits. It could be built and sold inexpensively. It would resist a cruel battering against the side of a vessel, being made of a sturdy copper core covered with cork and canvas. Each of its thirty-five compartments were air and water-tight. And unlike lifeboats of the period with pneumatic tubes inside, it wouldn’t puncture.

Horace Carley’s invention did not earn him his fortune, or bring him widespread recognition. Days before his death, he received news that the Carley Life Float Company was close to sinking, due to competition from a rival shipbuilder, and ongoing tussles over patent rights.

Horace Carley died Christmas Day, 1918. He is buried at Forest Hills cemetery.

By Clare Sharpe

Museum staff member/webmaster

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum