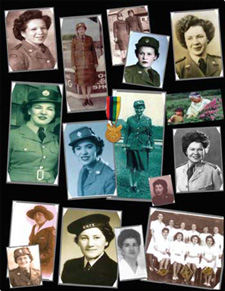

A collage of photos of Aboriginal women who answered the war-time call for recruits to serve Canada. Photo courtesy of Grace Poulin.

The year 2000 marked the 115th anniversary of women in Canada’s military, beginning with the nursing work in the Northwest Uprising 1885, the Yukon Field Force of 1898, and three contingents in the South African War 1899 -1902, with a permanent Nursing Service in 1901.

Although there was no official women’s corps in the Canadian military forces at the time, consideration had been given in 1918 to forming one, but no action was taken. Therefore, the only women to serve in uniform in World War One (WWI) Army Medical Corps were nurses.

It was not until 1941 that the Department of National Defence agreed that the services of women might be helpful, but they saw no urgency in mobilizing them. A contributing factor to the decision was control. Each branch of the service desired full control of any women’s service formed.

Initially, women’s services were auxiliary ones and even then, administrative difficulties led to regulation by individual branches and military law in 1942.

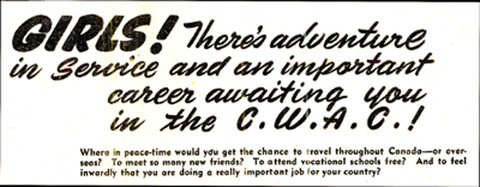

Recruitment came late in 1941, and was in full swing by 1942. Canadian women heeded the call to enlist either from a sense of duty, for adventure, for further education, for travel or for economic reasons. These women were pioneers of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC). They battled against objections to enlistment by families and boyfriends, and continued to battle negative attitudes from within the services after enlisting. One argument against women in the armed services was that military involvement went against the prevailing societal attitudes towards traditional female and male roles. These attitudes included the fear of loss of femininity, and that close-quartered work with men would lead to promiscuity.

Loss of female virtue was a very great concern, mostly to males who promoted the idea throughout the public domain. Domesticity was central to society’s gender ideology of the time, even though many women had to work outside the home to keep families together.

However, the National Film Board (NFB) delivered a vastly different message and encouraged women to enlist. The NFB was established as an agency of government propaganda at the beginning of the war and its films entreated women to enlist or to work on assembly lines. The aim was to convince the public that it was essential and acceptable for women to do these things. Powerful propaganda slogans prevailed: “We Serve that Men May Fly”, “We Serve that Men May Fight” and “We Are the Women Behind the Men Behind the Guns”.

Canada’s Armed Forces began recruiting women in 1941. Although women in paramilitary groups all over the country had been ridiculed and laughed at, they quickly answered the call to duty. Women’s treatment when appearing in uniform sometimes was severe. “My relatives viewed it [uniform] with absolute horror. Old family friends actually crossed the street rather than meet me in uniform. That was a very great hurt. A lot of men snickered behind their hands and a lot of mothers thought it was degrading.”

Initially, women required three references to be accepted – from a clergyman, from a businessman and from a non-relative – but requirements were relaxed as the war progressed. Many servicemen resented having girls in uniform. Reactions and attitudes towards women in uniform were not localized to any specific area but in Quebec, one Curé said “those ‘whores’ aren’t welcome in my church.”

Although the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) did accept Métis and enfranchised Indians, all of whom were as much Indian as those under the Indian Act, many Registered (Status) Indians felt the discrimination of the Royal Canadian Navy with its initial “colour barrier”.

The Naval Service maintained an official policy that required personnel to be of “Pure European Descent and of the White Race” before an application would even be accepted. There were three reasons given for this racial policy. Firstly, officials claimed that the confined living quarters of the Navy did not lend themselves to the mixing of White and Indian races. Secondly, the Navy issued daily rations of rum (grog), an old tradition of the Royal Naval Service, and since it was illegal for Indians to consume or buy alcohol, officials said this would stimulate ill-feelings among the Indian servicemen. Thirdly, other races such as Asians employed on “big” ships worked as stewards and servants but dined apart from the Whites. His Majesty’s Naval Service Regulations for “Maltese, Foreigners and Men of Colour” stated, “Only men and boys who are sons of British-born subjects are to be entered or re-entered in any branch of Naval Service.”

Although this policy pertains to enlistment, the fact that races other than white were employed on the ships suggests that Canadian Indians were treated differently than other racial groups. The Dominion Navy’s parent was the Royal Navy and common traditions, regulations and policies derived from it. The transfer of vessels and personnel between the British and Canadians was common and thus reinforced the Anglo-Saxon standard.

However, the RCAF had changed its regulations requiring recruits to be British subjects and of pure European descent very early in 1939 and accepted North American Indians. More Aboriginals served in the RCAF than the RCN, but due to education restrictions and health standards the number of Aboriginals was small. The required education level disqualified many Aboriginals who had advanced to only Grades One to Three in residential schools, but the RCAF’s relaxation of education standards in 1941 allowed for higher Aboriginal enlistment.

In 1943 the Privy Council resolved that “the Army and Air Force are accepting for Active Service personnel of any racial origin. It is essential that the Canadian Naval Service adopt a similar policy” and the RCN was ordered to allow admission of persons of any racial origin. Consequently, the Navy accepted Status Indians for the last two years of the war. The Regulations for the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service stated that “candidates must be British subjects, between 18 and 45 years of age, except specially suitable candidates under the age of 50, and in the case of cooks, under the age of 56 years.” Also, candidates had to be “free from physical defects, well developed according to age, sturdy, full chested, of good countenance expressing health and intelligence.”

Since some societies had women warriors, women in warfare was not a new concept to Aboriginal peoples, and Aboriginal women heeded the call to WWII service as did their non-Aboriginal sisters. They enlisted from reserve communities, farms, towns and cities across Canada. Since most women enlisted from 1942 onward, there is no documentation reporting enforcement of the policy “Of Pure European Descent and of the White Race.”

Their stories have common threads. Aboriginal women dreamed the same dreams as other women in that they were seeking adventure; seeking economic stability after the Great Depression; seizing a chance to get away from home; following brothers, uncles or fathers into the service; and hoping to further their education. All the women felt some trepidation upon enlistment, due to the physicality of basic training, the separation from family and friends, the discipline of regulations, and the snide remarks of males and the general public. Their concerns were offset by pride in their uniforms and contributions to Canada’s war effort.

There are reports of overt sexual assaults and many of gender bias. It seemed to depend on where the women were posted or how many ‘old boys’ officers they encountered. As with most of the female volunteers whose work was trivialized and whose contributions were generally assumed to be unimportant, dreams of going overseas never materialized and the duties were mundane and routine. Almost all women, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, served in medical, clerical, culinary or service roles that fitted male expectations of women’s roles in the work force, and they served at a pay scale lower than that of men.

Aboriginal women overwhelmingly felt that the military experience was good for them and it offered a personal growth that otherwise might not have been afforded. It also gave the women feelings of accomplishment and confidence in themselves. As with other servicewomen, returning home following discharge led to some feelings of unrest and being out in left field, not knowing quite how to get it together. For some there were feelings that no one else was particularly interested in their experiences and stories.

Servicewomen got on with their lives after the war by marrying, having babies, and raising families, and not by sitting around swapping military experiences. Often, families and friends didn’t want to hear what the women had done. They were expected to just get on with it. Because alcohol was served, Royal Canadian Legions were inaccessible to Status Indians following the war so they did not have access to comrades as did the non-Aboriginal population. Besides, at that time in history women were not allowed in pubs unescorted. Also, some Royal Canadian Legion branches did not allow servicewomen to join their membership but relegated them to Auxiliaries.

Aboriginal women who served in the Canadian military during WWII had very similar hopes, dreams and experiences as their non-Aboriginal sisters. Some women received the same benefits that were awarded other female veterans but others did not. Educational level played a large role as to which duties women were assigned, and the duties were as the military of the time saw female roles in society. Were their experiences as exciting as the men’s? Probably not to men, but to the women they were somewhat exciting, demanding, difficult and certainly different from mainstream civilian women.

Although some of the participants did not remember encountering prejudicial attitudes or behaviours while serving, it is evident that discrimination did exist in certain policies and sometimes in social relations. Perhaps some did not encounter it directly because they were perceived as non-Aboriginals and if they witnessed discrimination towards Black enlistees they certainly would not divulge that they were of Aboriginal heritage. However, racial discrimination did occur, subtly by innuendo about Blacks or Indians. One Aboriginal servicewoman recalled being left in the middle of the dance floor after her partner discovered her heritage. Another enlistee recounted suffering actual physical abuse by a comrade who stuck a lit cigarette on the side of her nose.

Aboriginal women dedicated part of their youth to a country that had fundamentally changed their lives through the Indian Act, the imposition of a Euro-Canadian value system through residential schooling or government oppression, the ‘whispering campaign’, loss of benefits and discrimination. While women’s voices in general have been muffled in the historiography, Aboriginal women’s voices have been doubly muffled, their standpoint and core beliefs and knowledge ignored, their voices silent. The lack of historical records on Aboriginal women’s lives, especially about their military service, underscores the neglect of their contribution to the history of Canada.

If “Women [were] the invisible combatants of WWII“, as stated by D’Ann Campbell, Aboriginal women were more invisible. Mistaken for European descent, many went unnoticed as being from the ‘Original’ peoples of what is now Canada, and while the women may not have emphasized their heritage to other military personnel, it has become a source of pride today. Because men did the actual fighting and all leading figures were men, women’s contributions were generally assumed to be unimportant, as with all things women did. But as unimportant as it may seem to some, Aboriginal women did leave their homes, their families and their cultures to enter the foreign milieu of non-Aboriginal culture and military.

Although they were treated equally while in military service, Aboriginal female veterans, like their male counterparts, were mistreated following war service by not being informed of available benefits or being ineligible for those benefits. Present-day redress has not necessarily met with the veterans’ approval. It is long overdue to express gratitude for their contribution to the tapestry of Canadian history.

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum