A brief history of

Caution: This article contains dated, biased and/or racist language.

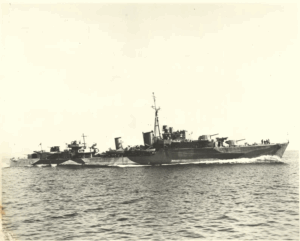

HMCS IROQUOIS 1 was the first “Tribal” Class destroyer to commission in the

Royal Canadian Navy and her arrival marked a new departure in naval warfare for the

rapidly expanding Canadian navy. As far back as the dark days of 1940, 2 when the

RCN comprised little more than a scant force of some six pre-war “River” Class

destroyers, and even before the first stalwart corvette had made her way to sea,

Canadian naval planners were beginning to think in terms of an offensive strategy which

would carry Canada’s war at sea to the very doorstep of the enemy. Aggressively

armed, the Tribals were designed as hard-hitting, swift-moving ships of war which would

operate with the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet destroyers in the North Atlantic and in the

danger-studded waters about the British Isles.

IROQUOIS’ keel was laid down in the Vickers-Armstrongs Yard at Newcastle-on-

Tyne on 19 September, 1940. The following year, on 23 September, she was launched

by Mrs Vincent Massey, wife of the High Commissioner for Canada. A disappointing

series of delays, occasioned by the shortages of material and labour in beleaguered

Britain, postponed her eventual commissioning date for still another year. The main

body of IROQUOIS’ company began to arrive in the United Kingdom in October 1942

and were accommodated in HMCS NIOBE. Courses were arranged at RN

establishments for a large proportion of the personnel, since many of them had had little

or no previous experience in destroyers.

On Monday, 30 November 1942, at Newcastle, under the command of

Commander W.B.L. Holms, RCN, and with the Naval Chaplain on the staff of the Flag

Officer-in-Charge, Tyne, officiating, IROQUOIS was commissioned in the RCN.

IROQUOIS passed the first nine days of December 1942 storing ship and

carrying out preliminary power trials. On 11 December the destroyer proceeded from

Methil on the Firth of Forth for the windswept Royal Navy anchorage at Scapa Flow,

“where all seems devised for the welfare of ships and the discomfort of men”. Upon

arrival, 12 December, IROQUOIS came under the administration of the Rear-Admiral

(Destroyers) Home Fleet for working-up exercises. During “work-ups” in the turbulent

winter waters off the Orkneys, weaknesses in IROQUOIS’ hull structure began to

appear. On 29 January the destroyer returned to North Shields on the Tyne where four

weeks were required to make good the damage and install additional stiffenings.

Work was completed by 24 February 1943 and IROQUOIS shaped course for

Londonderry whence she sailed independently to Halifax for examination by dockyard

and building officials who were to begin construction of Tribal destroyers in Canada.

Unfortunately, the ship had run into heavy weather off the Grand Banks of

Newfoundland and upon her arrival in Halifax on 6 March it was again found necessary

to dock the ship for repairs.

Many of the difficulties which had plagued IROQUOIS during her long and

tedious “work-up” resulted from the fact that since the original tribal structure had been

developed by the Admiralty, a vast amount of new equipment and armament had been

added and the ship’s hull had not the strength to carry it. It was not until IROQUOIS

had been adequately strengthened that this trouble was finally overcome. The RCN

Tribals which were later built in Canada were stiffened during construction. But

IROQUOIS, Canadian pioneer in the “Tribal” Class of destroyer, was to experience to

the hilt all the frustrations, set-backs and tribulations which accompany inevitably the

adoption of a new class of warship.

At noon on 15 March, IROQUOIS left Halifax for the return voyage to Britain,

stopping en route for a brief call at St. John’s, Newfoundland. Shortly after proceeding

out to sea, on 19 March, the destroyer ran into a severe north-westerly gale. At the

height of the storm, two of IROQUOIS’ men, attempting to go to the aid of an injured

shipmate, were washed overboard and lost.

Arriving back at Scapa on 24 March, IROQUOIS was allocated for service with

the Home Fleet and the next three weeks were taken up with exercises in northern

waters. During the latter part of April 1943, IROQUOIS was employed on close escort

duty with such mighty warships of the British navy as the battleships King George V and

Malaya. While in company with the latter, on 24 April, IROQUOIS ran into her old

bugbear, heavy weather, sustaining damage which put her back into dry dock again,

this time at Devonport. During her period in dry dock, the severely-tried destroyer was

subjected to still further damage when an RAF barrage balloon, which had broken from

its mooring during a gale, landed on the ship just abaft the after-funnel carrying away

the wireless antenna.

On 3 June IROQUOIS became operational again and, having been transferred to

the Plymouth Command, proceeded to sea in company with the Polish destroyer Orkan

and HMS Wensleydale to provide an anti-submarine escort for the RN battleship

Ramillies bound for the Clyde. The remainder of the month passed in a busy round of

activity, escorting Gibraltar-bound convoys out to sea and returning with incoming ones.

On 9 July 1943, IROQUOIS sailed as part of the escort for the liners California,

Duchess of York and Port Fairy, bound from Britain to Freetown, Sierra Leone, where

the transports were to embark troops for service in the Middle East.

Towards evening on 11 July, the convoy and its escorts were steaming a zig-zag

course some 300 miles west of Vigo, Spain, in calm, cloudless weather. At 2035 an

enemy plane was sighted, shadowing the convoy and hovering just out of gun range.

Half an hour later it was joined by two more Focke-Wulfs and shortly afterwards the

planes came in to the attack, down sun, from the north-west. The aircraft concentrated

their attacks on the troop transports California and Duchess of York which were shortly

mortally ablaze. IROQUOIS was singled out for attack at 2136 but a heavy barrage

from her 4” high angle guns and multiple pom-pom forced the plane to alter sharply

away. Three minutes later another Focke-Wulf came in for a second attack on

IROQUOIS. Her Captain ordered “full ahead” and violent avoiding action was taken; the

bombs fell harmlessly astern. The enemy then withdrew eastwards leaving the escort

(two destroyers and a frigate) to carry out the difficult and arduous task of rescuing

survivors. Submarines were known to be in the vicinity and at first IROQUOIS, then the

RN frigate Swale, who joined the group from Gibraltar, carried out an anti-submarine

sweep during the rescue operation. Together the escorts succeeded in picking up

some 1880 survivors, 660 being accommodated in IROQUOIS. The ship’s company

performed throughout the ordeal with great skill and determination; many feats of

gallantry and devotion to duty were noted by the Commanding Officer. At 0135 on the

12 th , having given orders to Moyala to sink the hulks of the Duchess of York and

California with torpedoes, IROQUOIS shaped course for Casablanca where the

survivors (some of them seriously wounded) were disembarked. Commander Holms

and two of IROQUOIS’ crew were afterwards presented with the Czechoslovak Military

Cross for rescuing nine Czechoslovak officers borne in the troop ships.

Before she left Casablanca, the destroyer embarked one German officer and five

ratings to be landed in the United Kingdom. These prisoners were survivors of U-506, a

740-ton enemy submarine which had been sunk on 12 July 1943 by a US Liberator

aircraft operating from the Gibraltar area. They had been picked up by HM Destroyer

Hurricane and conveyed to Casablanca. It is interesting to note that their Commanding

Officer, who did not survive the sinking, had claimed to have sunk, during the three

patrols he did in the submarine, seventeen ships, totalling in all 99,961 tons. 3

IROQUOIS, on the evening of 19 July, proceeded to sea in company with her sister ship

HMCS ATHABASKAN and the Polish destroyer Orkan, with orders to carry out a sweep

against enemy submarines and shipping in the Bay of Biscay. The group patrolled in

the “Musketry” 4 area of the bay. At 2225 the 21 st , IROQUOIS sighted a Spanish fishing

vessel to the eastward, the Monolo of Corunna, and, on being instructed to sink her, did

so after embarking her crew of fourteen. At 0827 the following morning, IROQUOIS

sighted and sank another, the Isolina Costade, while a third, the Vivero, fell a victim to

Orkan’s guns. These vessels were sunk in an area which had been prohibited to them

by Admiralty several months before because there was good reason to believe that they

were less interested in fishing than in the more profitable occupation of spying. In the

southern Bay of Biscay approaches, where British shipping movements were important,

there was ample opportunity for it. Warnings had been issued repeatedly by broadcasts

and leaflets dropped by aircraft, as well as by intercepting British warships. This was

the first action taken against them to enforce the orders.

Westward of the area about fifteen more fishing vessels were sighted spread

over a large area. As they were not in a position likely to prejudice the success of the

operation, they were not molested.

The following day Orkan fired on a lurking Focke-Wulf 200 aircraft and drove it

off.

On the afternoon of the 24 th , the group were directed by a Sunderland to a

position where they found a raft containing five survivors of U-558 which had been sunk

by aircraft on the 20 th . Dead bodies in life-belts were also seen in the area. During the

early morning of the 25 th , survivors of U-459, sunk by the RAF, were rescued. These

were made up of five officers and thirty-two men. Survivors of a Wellington aircraft

which had been shot down during the action against this submarine, were also sought

by the group. IROQUOIS, some three miles from Orkan found the aircraft’s dinghy. In

it was the tail-gunner, but four other reported survivors were not seen. 5

Upon completion of this mission with the Plymouth Command, IROQUOIS was

despatched northwards to rejoin the Home Fleet. Her arrival at Scapa was delayed,

however, due to another period in dock, this time to repair damage sustained while in

collision on 28 July with the trawler Kingston Beryl in the Irish Sea. Arriving at Scapa on

26 August, IROQUOIS was assigned to the desolate “Murmansk Run”, the treacherous

route to North Russia, where bitterly needed supplies for the hard pressed Russian front

were convoyed through waters daily searched by Nazi U-boats and aircraft and

menaced by German battleships and cruisers.

IROQUOIS’ first assignment (Operation “Holder”) into Arctic waters was not,

however, carried out as convoy escort but as part of a special naval force despatched to

North Russia with vital war supplies, a number of important passengers and mail for

British personnel at Polyarnoe, North Russia. The destroyers IROQUOIS and HURON

with HMS Onslaught, left Scapa on 1 October for Skaalefiord in the Faeroes, where,

after refuelling, they shaped course for Kola Inlet. The destroyers arrived at Murmansk

at 0200 on 6 October and, after speedily disembarking passengers and cargo, sailed

again at 2215 on the same day, carrying with them several members of the Russian

diplomatic corps.

Back in port only two days, IROQUOIS was sent out again to take part in

operation “F.Q.”. This operation was designed to carry relief personnel and stores to

the garrison at Spitzbergen and it was timed to coincide with operation “F.R.” (the

passage of a number of Russian minesweepers and small A/S vessels to Murmansk) so

that the heavy covering naval force would be available for both operations. IROQUOIS,

with HMCS HAIDA, HM Ships Vigilant, Janus, Hardy and USS Corry, formed the

destroyer screen for the British battleship Anson, the fleet carrier USS Ranger and the

cruiser HMS Norfolk, which comprised the support force.

On 27 October IROQUOIS was ordered to the Clyde to pick up the destroyer

depot ship HMS Tyne and escort her back to Scapa. After her arrival back at base on

the 30 th , IROQUOIS lay alongside Tyne until 5 November cleaning boilers.

In operation “F.T.” which occupied the next three weeks, IROQUOIS, with her

sister Tribals HAIDA and HURON, formed part of the destroyer flotilla under HMS

Onslow assigned to escort convoy JW-54A to Russia and convoy RA-54B on the return

journey. The convoys to North Russia had been discontinued during the summer

months of 1943 and JW-54A was the first one to sail when they were resumed in

November of that year.

JW-54A, consisting of 19 merchant ships, left Loch Ewe on 15 November. Its

progress was impeded by a north-westerly gale on the first day out and though U-boats

were known to be in the vicinity, all ships arrived safely. 6 On 26 November IROQUOIS

was alongside at Polyarnoe, when a Russian submarine, returning to her base at the

end of a 21-day patrol, entered the harbour firing a salute of four guns. The Admiral in

charge explained to the curious Canadians that this salute was to indicate that the

submarine had been successful in sinking four enemy ships. In keeping with a Northern

Fleet custom, the Admiral further elaborated, four pigs and a liberal amount of vodka

would be immediately bestowed upon the submarine’s crew.

On Christmas Day, 1943, the four Canadian Tribals were at sea escorting

convoys on the “Murmansk Run”. ATHABASKAN was part of the close escort for RA-

55A, returning from Kola Inlet to Britain and IROQUOIS, HAIDA and HURON were on

escort duty with JW-55B, the third convoy in the new series destined for Russia and the

fateful convoy which was to lure the Scharnhorst to her destruction.

Unhappily for Grand Admiral Doenitz, Commander-in-Chief of the German navy,

who reasoned that since two convoys had already passed unmolested by German

forces, the enemy would probably be less prepared for trouble, a heavy British battle

fleet had put to sea to reinforce the passage of north-bound JW-55B and home-bound

RA-55A. Ironically enough, the suspicions of the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet,

flying his flag in the battleship HMS Duke of York, had been aroused by the very ruse

which the enemy had employed to trap them. On 23 December Force 1, comprising the

RN cruisers Belfast, 7 Norfolk (who had stalked the Bismarck to her doom) and Sheffield

had steamed down the Norwegian coast from Kola Inlet in the event the Scharnhorst,

hidden in her anchorage at Altenfiord, might be tempted to come out.

At 2300 on the same day, Force 2 8 steamed out of Akureyri, Iceland, ready to do

battle if the German raider should put to sea. The Scharnhorst, blithely unaware that

any capital ships were in the area, departed Altenfiord escorted by the German 4 th

Destroyer Flotilla at 1900 on 25 December. It was to be her last sortie into the North

Atlantic.

During the next twenty-four hours Scharnhorst twice attempted to close convoy

JW-55B and twice was driven off by the accurate gun-fire of the British cruisers in Force

1. From their station as close escort for the merchant ships the Canadian tribals

watched with understandable concern the glow of the fire-works over the horizon. At

this point HMS Onslow, Senior Officer of the convoy escort, passed the code word

“Strike” – the order for the destroyers to form up on their divisional leaders for a torpedo

attack. This order was cancelled shortly afterwards when the Scharnhorst retired.

Despite the fact that the German battle cruiser possessed fire power far superior to the

British cruisers present, (who endeavoured to hold Scharnhorst until the Duke of York,

hurrying up from the south-west, could engage her) the Nazi warship chose to rely on

her superior speed and fled. Not, however, that the Scharnhorst was in any way lacking

in gallantry. As the only capital ship in northern waters in operational readiness, she

was under orders from Doenitz not to risk destruction in a duel with heavy ships. When

the superior guns of the Duke of York finally caught and crippled her, Scharnhorst went

down, about 60 miles north-east of Norway’s North Cape, with her colours flying and all

guns that had not been disabled still firing.

The convoy, meanwhile, proceeded on its way. Constantly shadowed by both

German U-boats and aircraft, the merchant ships were all brought safely into Kola Inlet

on 29 December.

As the year 1943 drew to a close, IROQUOIS could look back on the first six

months of her operational career with a feeling of satisfaction. Her ship’s company was

surely and firmly welding the destroyer into a first class fighting ship. 9 But IROQUOIS’

severest tests and greatest triumphs were to come in 1944 – the year of the invasion,

when the destroyer, in company with other Allied warships was to distinguish herself in

a series of night actions off the French coast particularly in the Bay of Biscay.

IROQUOIS arrived back at Scapa, after an uneventful return voyage with RA-

55B, on 8 January. Shortly afterwards she was transferred, along with HAIDA, to the

Plymouth Command in order to strengthen the naval forces pressing home the attack

against enemy shipping along the French coast and to establish a firm control of the

entire Channel area in readiness for the grand assault in June 1944.

From the 4 th to the 13 th of February, IROQUOIS, together with HAIDA and

ATHABASKAN, was recalled for duty with the Home Fleet to take part in operation

“Posthorn”. This was planned as an air strike from the carrier HMS Furious 10 against

enemy shipping in the shoal-studded waters between Stadlandet and Ytteröerne on the

Norwegian coast. The German coast-wise traffic off Norway was of great importance to

the enemy’s hold on the northern areas of that country for it was the primary means of

communication with the remote Nazi garrisons stationed there.

The three Canadian Tribals formed part of the destroyer screen for the heavy

support force consisting of the battleships HMS Anson and FS Richelieu and the RN

cruisers Belfast and Nigeria. 11

The hunt for enemy shipping, however, did not prove very fruitful and, no worth-

while targets being encountered by the aircraft, an attack was carried out on an

alternate objective, the beached SS Emsland. A merchant ship of 5,200 tons, the

Emsland had been damaged earlier by aircraft of the Coastal Command and was now

undergoing repairs. An attack was successfully carried out and the battle force returned

to Scapa on 12 February. None of the surface ships saw any action throughout this

operation.

On 18 February 1944 IROQUOIS departed Plymouth for Halifax where she was

to go into refit. While on passage, some 250 miles off the French coast, IROQUOIS’

asdic operator gave the alert that torpedoes were approaching on the starboard bow.

The destroyer was successfully manoeuvred to comb the tracks of the torpedoes,

believed to be “gnats”, 12 fired from a submerged U-boat.

After a brief stop-over at Horta in the Azores, IROQUOIS arrived in Canada on

26 February 1944. A refit began in Halifax which lasted until 28 May. On 1 June she

sailed for Liverpool via St. John’s, Newfoundland. She arrived back in England on 8

June, two days after D-Day, when the eyes of a tense world watched with hope and with

prayer as the Allied forces of liberation challenged Hitler’s Panzer divisions on the

blood-stained beaches of Normandy.

To IROQUOIS’ crew, secured alongside at Liverpool, undergoing intensive

courses in harbour training while new radar equipment was being installed, it must have

proved a frustrating time indeed. But plenty of action awaited her return to the Plymouth

Command and IROQUOIS’ company would have many occasions to sing the praises of

her new radar equipment.

On 1 August 1944 IROQUOIS sailed to rejoin the 10 th Destroyer Flotilla at

Plymouth. During this month the ship really hit her stride and her Commanding Officer,

Commander J. C. Hibbard, DSC, RCN, noted with pride in his report for August that:

“August 1944 has been HMCS IROQUOIS’ best

month since commissioning. The ship steamed a

total of 9,750 miles and spent 28 days at sea

carrying out anti-shipping patrols off the French

coast. Most of this time was spent within sight of the

French coast, and the majority of the nights at sea

ship’s company was closed up at Action Stations”.

IROQUOIS’ first operational assignment after her refit was a series of sweeps in

operation “Kinetic” 13 designed to destroy enemy shipping along the French coast. Early

in July it had become apparent that Germany meant to hold on to the west coast ports

along the Bay of Biscay as long as possible. La Rochelle, La Pallice, St. Nazaire,

Lorient and Brest, although no longer effective U-boat bases, since the Nazis had

begun withdrawing their submarines northwards to Norway, were still held by large

German garrisons which denied the Allies the use of these ports and harassed naval

operations in the area. Isolated by land, these garrisons continued to be slenderly fed

by sea, and operation “Kinetic” was designed with the object of permanently breaking

up their coastal supply links. Small merchant vessels, heavily protected by armed

trawlers, converted minesweepers, and occasionally by destroyers, crawled up and

down the coast in short hops by night, under cover of shore batteries and with the

added protection that the mined and rocky shoal waters gave to them. Even

discounting the danger of air attack from nearby air-fields, it was not a healthy place for

Allied cruisers and destroyers.

Force 26, consisting of the British cruiser Bellona (Senior Officer), the RN

destroyers Tartar and Ashanti and the Canadian tribals HAIDA and IROQUOIS, was

sweeping near Ile d’Yeu in the Bay of Biscay on the night of 5 August when radar

echoes of an enemy convoy working slowly to seaward of Ile d’Yeu were picked up.

The British-Canadian force held their fire until the moment when they could cut in

between the enemy and the land, and at 0034 on the 6 th the order was given to move in

and engage the enemy. When the action was broken off two hours later, the convoy

and its escort, believed to have totalled 8 or 9 ships, had gone down to almost total

destruction.

IROQUOIS’ Commanding Officer noted later in his account of the action that:

“A young and inexperienced ship’s company went

through their baptism of fire showing most

commendable steadiness such that the greatest

possible use was made of the opportunity presented

to achieve the object of destroying enemy ships.”

Survivors of the action who later were picked up stated that eight or nine hundred

special troops who were being evacuated in the coasters had gone down with their

ships. None of the Allied ships sustained any hits, but an unfortunate accident in

HAIDA, when a shell exploded upon entering the breach of one of her after guns, killed

two of her gunners and wounded eight more.

However, the damage to HAIDA was not crippling and Force 26 regrouped and

went into attack a second enemy convoy at 0335. The results of the second action

were inconclusive although some damage was believed to have been inflicted and the

convoy forced to put back to port. At 0630, with daylight approaching, Force 26 was

ordered by Commander-in-Chief Plymouth to return to harbour. As the group altered to

the westward to comply, IROQUOIS was detached to reinforce EG-2 and EG-11, 14

“hunter-killer” groups which were engaged in tracking down U-boats in the English

Channel. At 1611 on 6 August, while IROQUOIS was patrolling in line abreast with the

2 nd Escort Group, HMS Loch Killin destroyed U-736 in a brief single-handed attack with

her newly fitted Squid. 15 Three officers and sixteen ratings from this U-boat were picked

up and transferred to HMCS KOOTENAY for passage to Plymouth. 16

On the night of 14/15 August 1944, IROQUOIS took part in another operation

against enemy shipping in the approaches to La Rochelle. On this occasion IROQUOIS

formed part of Force 27 with the British cruiser Mauritius (Senior Officer), and the

destroyer HMS Ursa.

A small enemy convoy rounding Les Sables d’Olonne on a southerly course was

engaged at 0305 on the 15 th . In the brilliant bursts of Force 27’s star-shell, the enemy

was revealed as two merchant vessels and an Elbing destroyer. At once, the destroyer

turned to cover the convoy with smoke, at the same time firing a broadside of

torpedoes. All torpedoes passed harmlessly ahead of IROQUOIS. Immediately

afterwards, shore batteries on Les Sables d’Olonne and Ile de Ré opened a hot and

heavy barrage of fire against the Force. The fire was uncomfortably accurate, but by

good fortune all of the Allied ships escaped damage. At the end of the engagement the

two merchant ships were burning fiercely but the destroyer, having suffered a number of

hits, escaped at high speed.

At 0335 the Force was reformed and a northerly course resumed. An hour later,

IROQUOIS’ radar (which performed with remarkable efficiency during these operations)

picked up another contact at six miles. This proved to be a small tanker which was

repeatedly hit by all three ships until it had run itself aground. Towards morning, at

0620, a convoy of several ships crawling down the coast east of Ile d’Yeu was engaged

by the destroyers, the shoal waters being too treacherous in which to risk the cruiser.

The enemy, believed to consist of two merchant ships escorted by two “M” Class

minesweepers, returned the fire with much spirit. The enemy ships, however, were

quickly silenced and, as Force 27 withdrew, the ships, burning heavily, had beached

themselves. At 1015 on 16 August the Force shaped course to return to Plymouth,

well-pleased with the results of their patrol:

2 medium merchant vessels set on fire, beached and

destroyed.

1 small tanker beached and destroyed.

2 “M” Class minesweepers destroyed.

1 small merchant vessel or “M” Class minesweeper

set on fire and damaged.

1 “Elbing” destroyer damaged, but escaped, no other

vessels escaped. 17

The following week, on the night of 22/23 August, IROQUOIS took part in her

final assignment with operation “Kinetic”. Again with Mauritius and Ursa in Force 27,

IROQUOIS sailed from Plymouth at 1630 on 20 August with orders to carry out an

offensive patrol in the Bay of Biscay. Throughout the morning of 21 August the Force

patrolled in the vicinity of Ile d’Yeu and in the afternoon proceeded into the area near

Les Sables d’Olonne to confirm the results of the previous week’s action.

The patrol throughout the next two days was quiet except for a brief burst of fire

from the battery in the approaches to the Gironde River which straddled both

IROQUOIS and Mauritius on the morning of 22 August. Towards evening the Force

turned in towards Audierne Bay, the only area where enemy forces proceeding from

Brest to Lorient could be intercepted with some measure of sea-room.

At 0117 on the 23 rd , IROQUOIS obtained a contact close inshore off Pointe du

Raz. Force 27 stood out to sea for a tantalizing 20 minutes to let the enemy get well out

into the bay. IROQUOIS was then ordered to lead the ships in, in line ahead, followed

by Ursa and Mauritius. Fire was opened at 0209 at a range of 4,000 yards. Star-shell

illumination revealed an enemy convoy of two armed merchant ships, one “M” Class

minesweeper and a flak ship.

According to Mauritius’ account of the action:

“The enemy immediately made smoke and turned to

give an end-on target, returning Force 27’s fire with

spirit. The shore battery at Audierne joined in, but on

the whole their fire was ragged and inaccurate. One

medium sized merchant ship was hit almost

immediately by Mauritius, blew up and sank at once.

The remaining three ships were repeatedly hit, one

trawler being driven aground on fire in the entrance

to Port Audierne. The second merchant ship was set

heavily on fire and sank close westward of the reef

off Port Audierne. The minesweeper was stopped,

damaged and aground, not many hundred yards

from the place Captain Pellew, with two frigates in

1797 drove the French 80-gun Ship-of-the-Line

Droits de L’Homme ashore, causing over 1,000

French sailors and soldiers to perish.” 18

Forty minutes later the destroyers formed astern of Mauritius and altered course

to the south-west to search for any other convoy which might be attempting to cross the

Bay of Biscay. At 0336 IROQUOIS’ radar again picked up a firm contact moving on a

south-easterly course. Again the Canadian destroyer was ordered to lead the Force in

to intercept. Fire was opened fifteen minutes later against an enemy force of two armed

trawlers, one minesweeper and one sperrbrecher. 19 By 0455 the entire enemy force

had been destroyed. A boarding party from Ursa was later sent aboard the

minesweeper aground on the shoal off Port Audierne. Eleven prisoners were taken

along with various charts and documents. It was afterwards learned from the French

Forces of the Interior at Penmarch that some 150 Germans fleeing from the burning

ships had been captured by them. It was a good night’s hunting and when the final tally

was made the score stood at: five armed trawlers, one sperrbrecher, one coaster and

one flak ship sunk. 20

IROQUOIS’ activities off the coast of France during the last week of August 1944

constituted a relatively peaceful assignment. She was ordered to patrol in the Bay of

Biscay and to land armed parties at various points along the coast and outlying islands.

Where the Resistance Forces (FFI) were strong, she was to establish liaison with the

leaders of the underground and gather intelligence information.

On the afternoon of 26 August, a party of four from IROQUOIS equipped with a

portable W/T set disembarked and went ashore at Port Joinville on Ile d’Yeu. The day

previous, the last of the German garrison had evacuated the island, taking with them the

Mayor and nineteen citizens for having weapons in their possession. Also, prior to their

departure, they had looted the local post office and wrecked all radar equipment on the

island, as well as the lighthouse, which was the third largest in France.

IROQUOIS’ men received a hearty reception from the FFI 21 and the 4,000 French

civilians on the island. The local population, anxious to show their pleasure, not only

co-operated to the full, but, with the last of their remaining store of food, entertained the

group at a party. There was a festive note in the air and Frenchmen everywhere were

eager to celebrate an occasion dear to their hearts. On this day, 26 August 1944,

General De Gaulle had made his triumphant entry down the Champs Elysées to mark

the formal liberation of Paris.

On the 27 th and 28 th of August IROQUOIS carried out similar landings at St.

Guenole on the Penmarch Peninsula where the FFI were very active. The landing

parties returned to the ship with valuable information concerning enemy movements,

the positions of shore batteries and the extent of mining in coastal waters.

IROQUOIS’ routine of watch-keeping off the Biscay coast was broken early in

September when the destroyer was detached on a special assignment, (Operation

“Octagon”), to act as destroyer escort, as far as the Azores, for the SS Queen Mary

bound for Canada. Among her valuable cargo of passengers the liner carried Prime

Minister Churchill, on his way to meet President Roosevelt for their second historic

meeting at Quebec.

Upon her return at Plymouth, IROQUOIS was taken in hand for boiler cleaning

prior to her return to the Biscay area.

A final assignment to land armed parties at Les Sables d’Olonne on the 23 rd and

30 th September 1944 completed IROQUOIS’ operations in the Biscay area. On the 16

October she departed Plymouth, detached from the 10 th Destroyer Flotilla and

temporarily transferred to the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow.

Three weeks later, on 6 November, IROQUOIS was back under the operational

control of Commander-in-Chief Plymouth where she remained until the middle of March

1945. Throughout this period the destroyer operated on detached duty as close escort

for capital ships and troop transports in the dangerous coastal waters off the British

Isles where schnorkel-equipped U-boats now lurked.

Prior to the general introduction of schnorkel in the summer of 1944, only the

boldest of U-boat “aces” dared to traverse these in-shore waters where their chances of

escaping unscathed were slim indeed. Schnorkel revolutionized the tactical grounds on

which the submarine war was fought. Operating often in defiance of Allied air power, it

threatened one of the pillars on which ascendency over the Nazi underwater fleet had

been built. Between the 18 th and 28 th December 1944, two enterprising U-boat captains

patrolling in the English Channel, sank eight ships – a small number in comparison with

the vast volume of shipping which now ploughed the convoy lanes in support of the

advancing armies of liberation, but what was disquieting was the fact that they escaped

to tell of their success. Their immunity to air and surface attack aided by the difficult

asdic conditions prevalent in in-shore waters, the U-boats, on the eve of the Allied

victory in Europe, were enjoying their greatest successes since the brisk spring of 1943.

After a busy winter on close escort duty, IROQUOIS spent a short period boiler

cleaning at Plymouth early in March 1945. On 16 March she departed for Scapa Flow

to take part in a series of operations with units of the Home Fleet.

IROQUOIS sailed from Scapa for the first of these operations (“Cupola”), on 19

March, as part of Force One 22 detailed to lay mines in the narrow waters off Granesund

on the coast of Norway. The operation was successfully carried out on the 20 th under

excellent weather conditions and without enemy opposition. The destroyers saw no

action and remained throughout in company with the heavy units standing about a

hundred miles out to sea beyond the enemy’s own mine barrier.

Four days later, on 24 March, IROQUOIS set out again from her base at Scapa,

this time as part of Force Two. 23 The operation 24 was planned as an air strike against

enemy shipping in the Trondheim leads, but, not finding any worth-while targets on the

morning of 26 March, the bomb-carrying Avengers attacked radar and other important

installations along the channels. On the morning of the 28 th a second strike was flown

off against several enemy merchant ships, two of them being set on fire. Although the

surface forces saw no action, three ME 109’s were destroyed in combat and one Allied

Barracuda aircraft was lost. 25

IROQUOIS, in company with the RN destroyers Onslow, (Senior Officer),

Zealous and Zest took part in a surface ship action (Operation “Foxchase”), against

shipping off the Norwegian coast 26 on 4 April 1945. At 0011 four medium-sized

merchant vessels, accompanied by three escort vessels, were engaged in a vigorous

exchange of gun-fire. All the destroyers scored hits on the convoy which promptly

altered course and made for shore. Unfortunately, the Senior Officer, believing that the

danger from E-boats and submarines in the vicinity (IROQUOIS reported two on the

surface at 0035) made the battle area too hot for the destroyers, gave orders to

withdraw to seaward. Intelligence reports later revealed, to the disappointment of the

Force, that no enemy ships had been sunk and none seriously damaged.

IROQUOIS’ next assignment (Operation “Roundel”) took her back to the familiar

convoy route to North Russia. With her sister Tribals HAIDA and HURON, IROQUOIS

formed part of a heavy force 27 detailed to escort JW-66 28 to Kola Inlet.

Although the inevitable surrender of German forces was now, after six years of

bitter conflict, close at hand, and everywhere in Europe Nazi strength was shrinking to

the battleground around Berlin, at sea, the enemy’s submarine flotillas still fought with

much of their old skill and daring. On 22 April 1945, three days before the destroyers

shepherded JW-66 safely into the anchorage at Vaenga Bay, two merchant ships had

been torpedoed and sunk close by the mouth of Kola Inlet. So it was that to the last day

of the war, 29 merchant ships had still to move in convoy and in the waters off Russia and

Norway the danger from U-boats remained as acute as ever.

Considerable enemy activity enlivened IROQUOIS’ return passage to Britain with

convoy RA-66. Shortly before the convoy departed (midnight on 29 April), frigates of

the Royal Navy 19 th Escort Group succeeded in destroying two U-boats, U-307 and U-

286, in the approaches to Kola Inlet. In retaliation, the enemy claimed one of the

Group’s frigates, HMS Goodall. Although RA-66 passed through the danger area

without loss, the going was hard, and both HAIDA and IROQUOIS reported “near

misses” by torpedoes. It was to be the last chance the enemy was to have at the

Canadian Tribals. The convoy arrived without loss at the Clyde, 8 May 1945, in time to

celebrate the Allied victory in Europe.

Only the fighting was over; much work remained to be done. On 9 May,

IROQUOIS was ordered to Rosyth where she formed part of the destroyer screen for

the British Force proceeding to Oslo, returning Crown Prince Olaf, after years of exile, to

his capital. Having completed this operation, IROQUOIS steamed for Copenhagen

where she joined the British cruisers Devonshire and Dido and the RN destroyer

Savage. On 24 May she sailed, as part of this force, to escort the German cruisers

Prinz Eugen and Nurnberg to Wilhelmshaven where they were to await their disposal by

the Allies.

For Canada’s Tribals, the job in European waters was drawing to a close. On 4

June 1945, HAIDA, HURON and IROQUOIS, in company, shaped course for Halifax.

Here the ship was to be taken in hand for tropicalization prior to her departure for the

Pacific where she was slated to join the British Fleet in the war against Japan.

IROQUOIS arrived in harbour on 10 June and two weeks later went into refit.

However, before this was completed, the Japanese surrender on the 14 th of August

brought the war in the Far East to an end.

Her refit complete by the middle of December 1945, IROQUOIS was allocated to

the Reserve Fleet early in the New Year. 30 She was paid off 22 February.

In three months time, on 27 May 1946, IROQUOIS recommissioned as Depot

Ship for the Reserve Fleet (East Coast), taking over the duties of Senior Officer Ships in

Reserve from HMCS QU’APPELLE whose crew transferred to IROQUOIS. Routine

care and maintenance on the destroyers in reserve was carried out by IROQUOIS’

company; all other maintenance was conducted by Reserve Fleet personnel borne in

the establishment ashore, HMCS SCOTIAN.

Throughout the winter of 1946-47, the three Tribals, HAIDA, HURON and

IROQUOIS, each a veteran of many gallant exploits in European waters, remained

secured alongside “jetty zero” in the sheltered waters of Halifax harbour.

In February 1947 when SCOTIAN was paid off as the administrative and

accounting authority for the Reserve Fleet IROQUOIS took over her duties, and the staff

of the Senior Officer Ships in Reserve (SOSR) transferred to IROQUOIS.

During the summer of 1947 the former Nazi U-boat, U-190, 31 having spent a brief

period in commission as an RCN submarine, was allocated to the Reserve Fleet under

the control of IROQUOIS while awaiting her final demise by RCN forces on 21 October

1947.

In November 1947, IROQUOIS was taken in hand for a series of refits, which

were not completed until a year and half later.

On 24 June 1949 IROQUOIS advanced from “Reserve” to “Operational”

Commission and Reserve Fleet personnel were transferred to HMCS LA HULLOISE

who succeeded her as Depot Ship for the Reserve Fleet.

After a great deal of last-minute bustle and preparation, IROQUOIS put to sea, 9

July 1949, with 101 UNTD cadets 32 borne aboard for training. Throughout July and

August the destroyer cruised along the eastern seaboard, putting in for brief visits at

Provincetown, Mass., New Haven, Conn., Saint John, N.B., and Corner Brook and St.

John’s in Newfoundland. Upon her return to Halifax, IROQUOIS was paid off into

Reserve Fleet on 3 September 1949.

On 15 June 1950, the program to install anti-submarine weapons in IROQUOIS

was begun. 33 A year and a half later, on Trafalgar Day, 21 October 1951, IROQUOIS

recommissioned under Commander W. M. Landymore, RCN.

A word on IROQUOIS’ badge would be in order here. This is founded on the

unofficial one prepared in 1942, which was in turn taken from a painting by the late C.

W. Jefferies. Depicted in gold is the head of an Iroquoian warrior, cut off at the base of

the neck, with the peculiar cock’s-comb “hair-do” and top-knot for scalp removal. There

is war-paint on the face, two eagle feathers in the hair and a gold ring pendant from the

ear.

Ship’s colours are black and gold. The motto, approved in August 1957, reads:

“Relentless in Chase”.

After an inspection by Rear-Admiral DeWolf who visited the ship to view her new

weapons, IROQUOIS steamed out to sea, 13 January 1952 for full power trials. On the

28 th she was sailed to Norfolk, Virginia, where she came under the operational control of

Commander Operational Development Force for evaluation trials.

The first week in February was spent at sea in the approaches to Norfolk carrying

out preliminary exercises. Here, on 6 February, the ship’s company was grieved to

receive the official announcement of the death of their beloved Commander-in-Chief,

His Majesty King George VI. Upon their return to the Norfolk Naval Base, a solemn

memorial service was held to honour the memory of the late Monarch.

On completion of her trials on 13 March IROQUOIS received the following

message from the American Commander in charge of her operational development:

“Congratulations on expeditious completion of trials.

Your efficient execution of all tasks and hearty

cooperation greatly admired. COMOPDEVFOR

appreciates opportunity to be shipmates with such a

fine Command.”

IROQUOIS returned to Halifax on 15 March and shipyard workers took her in

hand for final preparations prior to her departure to join the RCN forces in Korean

waters. Until the 5 th of April 1952 the destroyer was hauled out on the Dartmouth slip for

hull repairs, bottom cleaning and painting. Throughout the next two weeks the ship was

stored and ammunitioned. On 17 April IROQUOIS went to sea, flying the flag of Rear-

Admiral R. E. S. Bidwell, CBE, CD, RCN, for a day of full calibre firings. On 21 April,

having been assigned to the RCN Special Force, IROQUOIS was sailed for Korea. The

destroyer passed through the Panama Canal on 30 April and arrived Sasebo, Japan, by

way of Pearl Harbor, on 12 June 1952.

When IROQUOIS arrived in the operational area a few days later, the war in

Korea was already two years old. For the past twelve months, since July 1951,

attempts to reach a truce negotiation had been underway; unfortunately, with scant

success. If any anxiety was felt throughout the ship that they might not be in time to

“fire a gun in anger”, they could take some comfort from the knowledge that HMCS

CAYUGA, whom they were relieving in Korea, had felt the same misapprehension a

year earlier when she arrived in the area. However, even for those who wished that it

would, the war was not to be brought to an end for yet another year.

True, the bitterly fought see-saw operations, in which spectacular advances were

followed by staggering withdrawals, as first the Communists, then the United Nations

forces, parried for position in the nightmare struggle of advance and retreat, belonged to

the past. By July 1951, when the peace talks first began at Kaesong, the major battles

had been fought, the heaviest casualties suffered, the majority of the incredible number

of prisoners taken. Entrenched along the 38 th parallel, the armies faced each other

across the “no man’s land” of the buffer zone, each side ruthlessly defending his

position, cautiously probing for weak spots in the other’s defences.

From July 1951, until the armistice was signed on the 27 th of July 1953, the

military situation generally remained static. The bored reflection, “war is mainly waiting”,

was never more truly borne out than by these two years on the battleground of Korea as

the armies dug in to hold and survive while the seemingly endless “peace talks”

dragged on in the tents at Panmunjom. Savage outbursts of local activity flared up from

time to time as a rugged hill-side or a barren ridge became the object of dispute; and

men died, or were taken prisoner, or endured, as through two long years the “waiting

war” went on.

For the United Nations naval forces, the war was settling into a routine of

vigilance and blockade. The heavy naval bombardment in support of the UN forces

backed up at Pusan, the daring and spectacular amphibious landings at Inchon, the

assault at Wonsam, all belonged to the action-filled first year of the war in Korea; each

had taken its place beside the great “combined operations” of history.

After 1951 the Canadian destroyers in the Far East were committed to the task of

maintaining the UN’s “iron ring” about Korea. Primarily the naval task was a blockading

one. Local operations involved breaking up the enemy’s coast-wise traffic, the defence

of the friendly west coast islands, and the bombardment of rail installations which

skirted the foot of the cliff-bound east coast. Not a small part of the duty of RCN

destroyers was the screening of aircraft carriers for the telling strikes which were made

against enemy troop concentrations, supply dumps, bridges and other vital installations.

The monotonous task of screening duty, however, was frequently enlivened by orders to

proceed close in shore to bombard enemy shore positions or to assist guerilla forces in

landings along the shore or on outlying islands in order to gather intelligence and take

prisoners.

IROQUOIS’ first tour of duty in Korean waters lasted for five months and during

this period the destroyer, back in an active war zone for the first time in seven years,

and her first taste of fighting in the Pacific, was to carry out a varied program of

activities.

On 20 June 1952, she took over from ATHABASKAN, who was preparing to sail

home to Canada, the duties of Commander, Canadian Destroyers Far East. Her first

operational assignment, screening the American carrier USS Bataan, took her on 23

June up the west coast of Korea to the area of the hotly contested 38 th parallel.

Teaming up with HM Cruiser Ceylon and HM Frigate Amethyst, she made an attack on

the southern tip of Ongjin Peninsula. British planes, acting as spotters, directed fire on

the coastal defences in the approaches to Haeju and also called for fire on troops

digging in behind the coast. Enemy guns, on attempting to return the fire, were quickly

silenced by the concerted attack of the three warships. Every third night IROQUOIS

was detached to carry out in-shore patrols in the Paengyong Do 34 area under CTE

95.12, 35 HMS Belfast. While operating with IROQUOIS in the vicinity of the island of

Chodo on 5 August the British cruiser, veteran of many epic sea battles in the Second

World War, sustained a direct hit from an enemy shore battery.

After a period at Kure, Japan, for maintenance, IROQUOIS returned to the

operational area in the vicinity of Haeju on 30 August as Commander Task Unit 95.12.4.

On arrival off the peninsula north of Mu-Do a heavy bombardment of enemy positions

was carried out using shore fire control spotting teams and air spots from HMS Ocean.

The results, recorded IROQUOIS’ Commanding Officer, were “excellent”.

On the night of 3 September a tropical storm – “Mary” – moved into the area,

forcing the destroyer to withdraw to seaward. Apparently IROQUOIS found the China

Seas typhoon kinder than the winter waters off Scapa Flow for she rode out the storm

unscathed.

The following week, on 10 September, IROQUOIS together with the American

carrier Sicily took part in Operation “Siciro”, the code name being compounded from the

two warships’ names. “Siciro” was designed as an assault by three Wolf-pack

companies 36 against a point on the Peninsula of Chomi Do in the Bay of Haeju. The

guerilla forces, about 350 strong, were led by US army officers and NCO’s. The Wolf

packs pushed off from the island of Yongmae Do at 0100 on the 10 th . While the

assaulting forces borne in junks, some steam, some sail, were making the three-mile

passage across the mud flats to their objective, IROQUOIS’ gun-fire softened up the

edges of the peninsula. The British cruiser Belfast made a timely appearance in the

Haeju area and her offer to assist in the operation was not refused. IROQUOIS’

Commanding Officer described the 90-minute naval bombardment as a “battle of wits

between the Ships’ Gunnery Officers who wished to have a reasonable ammunition

expenditure and the spotter who was determined to empty our magazines as rapidly as

possible. A reasonable compromise was achieved and both the spotter and the ships

were satisfied with the outcome”. Sicily’s aircraft arrived at 0620 to lend effective

support to the withdrawal of the Wolf-pack forces, and by 0830 the junks, with the

assaulting force intact, were on the return journey to Yongmae Do. Enemy casualties

were reported later to be close to 400. Several gun positions had been destroyed and

three agents who had been in enemy hands were recovered and brought back. Four

South Korean Guerillas suffered light wounds. IROQUOIS’ Commanding Officer

summed up the venture with these words:

“One would have thought that “Siciro” carried out in

full moonlight, with uncertain water transport, with

semi-trained troops, led by officers who gave their

orders through interpreters and with a rather fuzzy

aim was doomed to failure from the start.

Astonishingly enough, almost everything happened

according to the plan and it turned out to be a

modest success.”

On 28 September IROQUOIS sailed from Sasebo for Yang Do far up the east

coast of Korea where she relieved HMS Charity on the 29 September. In the situation

report turned over to IROQUOIS, Charity had commented: “I had no hesitation

anchoring day and night when at Yang Do – this has been going on for fifteen months. I

don’t know how long the enemy will allow it to go on for.” The answer, IROQUOIS soon

found out, was “fifteen minutes”. No sooner had Charity weighed and proceeded than

the anchorage came under fire. The nearest shells missed IROQUOIS by some 400

yards, but the incident heralded the active days to come.

North Korea’s rail system ran north and south along the east coast of the

peninsula and it was in these waters that Canadian destroyers gained fame as ace

members of the “Train Busters Club”. Unfortunately, during IROQUOIS’ first operational

assignment in the area, she was to suffer the only RCN casualties of the Korean war.

During her patrol Charity had stopped a train by gun-fire at the coast’s edge, just

south-west of Sonjin. The line had been blocked for several days, and faced with

feverish attempts by the enemy to clear it, UN naval vessels were detailed in shore to

see that it remained blocked.

On the 2 nd of October, IROQUOIS, together with the American destroyer Marsh,

carried out a successful bombardment of the area. As the two ships turned to seaward

at the close of the engagement, shore batteries opened fire and shortly afterwards a full

salvo bracketed IROQUOIS. Despite her evasive tactics and an attempt to clear the

area at high speed, IROQUOIS sustained a direct hit in “B” gun position. The

destroyer’s guns replied and the shore battery was soon effectively silenced. Aboard

IROQUOIS, one officer and one seaman had been killed instantly. A second rating,

critically injured, died a few hours later. Ten other men were wounded. Her fighting

efficiency, however, was in no way impaired, and the destroyer, having transferred her

dead and wounded to USS Chemung, an American supply ship carrying a surgical

team, returned to complete her patrol in the area.

On the morning of 8 October, with a guard of honour drawn from HMCS

CRUSADER, Lieutenant-Commander John L. Quinn, Able Seamen A. E. Baikie and W.

M. Burden were buried with full naval honours in the British Commonwealth Cemetery

at Yokohama, Japan. At the same time, aboard IROQUOIS, ten miles to seaward of

where the action had taken place, Commander Landymore led a simple memorial

service in tribute to the fallen shipmates.

Back at the rail block on 9 October IROQUOIS carried out interdiction fire and

routine patrols until she was relieved by HMCS CRUSADER on 14 October when she

set course for Sasebo. During her brief period in dry dock the ship’s company was

inspected by Admiral Sir Rhoderick R. McGrigor, KCB, CBE, DSO, RN. IROQUOIS

undocked on 22 October and sailed for a week’s operations off the west coast of Korea.

On 1 November IROQUOIS was sailed in company with the RN carrier Ocean for

Hong Kong. On the morning of 4 November while the British carriers Ocean and Glory

combined for exercises to test the defences of Hong Kong, IROQUOIS acted as plane

guard for the operation. On the 9 th November, IROQUOIS represented the RCN at a

Remembrance Day Service at the Cenotaph and on the 11 th the ship’s company

paraded to the Military Cemetery for a purely Canadian Armistice Day Service. A

wreath was laid on the grave of an unknown Canadian soldier. At noon the following

day, IROQUOIS set course to return to the operational area. While on passage in the

Formosa Straits typhoon “Bess” overtook the destroyer and for three days and nights

she battled the storm. On the 16 th the veteran destroyer limped into Sasebo, badly

shaken up, but with no serious damage. Back with the west coast blockading forces on

the 19 th , IROQUOIS carried out bombardments against gun emplacements, observation

posts and cave positions with good results before returning to Sasebo on the 22 nd . Here

the ship was stored and final preparations made for the voyage home. IROQUOIS had

completed her first tour of duty in the Korean theatre. After a farewell visit from Rear-

Admiral E. G. A. Clifford, RN, IROQUOIS sailed from Sasebo on 26 November, bound

for her home port of Halifax via Pearl Harbor. As the ship would be at sea on Christmas

Day, the destroyer put into Esquimalt for a short stop-over on 16 December and half of

the ship’s company were granted leave which enabled them to be “home for Christmas”.

Leaving the west coast port on 20 December, IROQUOIS steamed south to Manzanillo,

Mexico, where she arrived on 27 December. After passing through the Panama Canal

on 2 January, IROQUOIS reached Halifax by way of Bermuda on 8 January. Here she

secured at the familiar “jetty zero” to undergo refit.

Three months later, on 29 April, 1953 IROQUOIS, in company with HMCS

HURON, was sailed for Kingston, Jamaica, the first leg of her return passage to the Far

East. The voyage was made uneventfully except for some engine-room difficulties

experienced by both Tribals off the west coast of Mexico. The trouble was eliminated in

IROQUOIS when fourteen buckets of shrimps were removed from her condensers.

IROQUOIS arrived at Sasebo on the 18 th of June. The peace talks, which had

dragged on interminably for almost two years, seemed now, at last, to be approaching

an armistice agreement. Unfortunately, the “release” of 25,000 North Korean anti-

communist prisoners of war on 18 June stimulated fresh outbursts of activity along the

eastern and central sectors of the front and with peace talks once again suspended, the

long-awaited truce agreement was postponed another five weeks.

On 19 June IROQUOIS sailed for the operational area and on reaching the

vicinity of Chodo, 22 June, took over the command of Task Unit 95.1.4 from HMS

Modeste. However, affairs on her west coast patrol were unusually quiet and the

destroyer, relieved by HMS Cockade on 27 June sailed for a courtesy visit to Tokyo

where the ship’s company enjoyed a lavish program of entertainment and hospitality.

Officers and men rose gallantly to several “unorthodox” occasions and the Commanding

Officer noted with pride that his officers, guests at one of the many official dinners,

“conducted themselves agreeably in spite of the shock of finding fisheyes in the

soup….”

IROQUOIS returned to the operational area 6 July when she joined the screen of

the American carrier Bairoko. On the 14 th IROQUOIS was detached to relieve HMS

Charity in the familiar Haeju area. Heavy fog necessitated a cancellation of all

bombardment plans and on the 19 th IROQUOIS, relieved by HMCS ATHABASKAN,

returned to Sasebo, where she secured alongside the destroyer depot ship HMS Tyne.

At 1000, on 27 July 1953, the Korean Armistice was signed 37 and at 2200 the

“cease fire” went into effect. For the United Nations ships in the Far East, however, the

job was not yet done.

Patrols continued to be carried out among the islands still under UN control, but

the warships steamed at night with their navigating lights on and their scuttles

undarkened.

In accordance with the armistice some UN-held islands north of the 38 th parallel

had to be evacuated. Cho-do, within eighty miles of the Yalu River on the west coast,

was one of these. IROQUOIS played an important part in the evacuation of this island.

Gear and installations had to be removed and there were twelve elderly persons

remaining there who had previously declined offers to be taken off. Two officers from

the ship went about renewing the offers. Two finally yielded to their urgings and six

weeks supply of food was left for the remaining ten. When the last landing ship tank

was loaded and had withdrawn from the beach, a demolition team of seventeen men

from the destroyer, headed by Lieutenant D. A. Wardrop, RCN, remained behind with a

similar group of US Air Force personnel,to blow up a few remaining installations. They

completed their work at 0500 on 1 August and the island was declared evacuated. 38

IROQUOIS remained in the area until the ten-day period allowed for adjustments

to the “cease fire” line had elapsed. On 6 August she assumed command of Task Unit

95.1.2. This truly international group of warships embodied a New Zealand frigate, an

Australian frigate, a Dutch frigate, several American minesweepers, a South Korean

patrol craft and a Royal Navy fleet auxiliary – a heterogeneous naval force which

provided, observed IROQUOIS’ Commanding Officer, “an almost continuous

pantomime on the Radio Telephone”.

Relieved by HMS Crane on the 14 th , IROQUOIS returned to Sasebo. During the

“uneasy truce” conditions which prevailed throughout the next eighteen months, when

the volatile prisoner-of-war question remained an explosive issue to threaten the

delicate balance of international relations in the Far East, IROQUOIS, and the other

Canadian destroyers who followed her, carried out peaceful patrols in Korean waters

with a view to ensuring that the conditions of the armistice agreement were adhered to.

As a training ground, IROQUOIS’ “tours of ops” in the Korean theatre proved

particularly valuable and, as with the other RCN destroyers in Korea, her fighting

efficiency showed a marked improvement in proportion to the amount of time spent in

the Far East. Several factors contributed to make this so. For one, the waters on

Korea’s west coast presented some of the most difficult navigational hazards to be

found anywhere in the world. Added to the maze of islands which dot the coast, are the

challenges of shifting mud flats and a tide that rises and falls 31 feet. Also the

opportunities presented for exercises with other navies of the United Nations provided

many invaluable lessons in group operations.

In October 1953 IROQUOIS left the operational area for Hong Kong where she

underwent her semi-annual docking. Here, at the Tai Koo docks, on 1 November,

Captain Landymore turned over command of IROQUOIS to his Executive Officer,

Lieutenant-Commander S. G. Moore, CD, RCN.

The destroyer returned to Sasebo 26 November and the following week

participated in exercises with HURON, CRUSADER, HMAS Tobruk and HMS Comus.

Towards the middle of December, IROQUOIS returned for a week’s patrol in the

Paengyang Do area where the Commanding Officer assumed the duties of Commander

Paengyang Do Island Naval Defence Unit.

Back at Sasebo at year’s end, IROQUOIS was relieved by HMCS CAYUGA 1

January 1954 and sailed the same day for Hong Kong, the first stop on her return

voyage to Canada. Prior to her departure the destroyer received a fine tribute from

Vice-Admiral R. P. Briscoe, USN, Commander of the United Nations Naval Forces in

the Far East:

“By your excellent performance in all tasks assigned,

you proved yourself a worthy and valuable member

of our naval team in the West Pacific. You are a

credit to your flag, your navy and to the United

Nations. Well done and sincere best wishes.”

On her homeward voyage, IROQUOIS called at Singapore, Colombo, Gibraltar

and Ponta Delgada in the Azores. Voyaging by way of the Suez Canal and the

Mediterranean she completed her first circumnavigation of the globe when she arrived

at Halifax on the morning of 10 February. 39

On 23 March 1954 command of the destroyer passed to Commander M. F.

Oliver, CD, RCN. By the end of May her refit was completed and the Tribal put to sea

for trials on the first of June. Rear-Admiral R. E. S. Bidwell, CBE, CD, RCN, informally

walked around the ship on 11 June and addressed the ship’s company. During the

evening of the 11 th , the Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant-General G. G. Simonds,

CB, CBE, DSO, CD, the Quarter-Master General, Major-General S. F. Clark, CBE, CD,

and the General Officer Commanding Eastern Command, Major-General E. C. Plow,

CBE, DSO, CD, were received on board for passage to St. John’s Newfoundland where

the CGS was to inspect the Newfoundland area of the Eastern Command. At the

instant of embarkation the GOC’s flag, suitably illuminated, was broken at the fore, for, it

is believed, the first time in Canadian naval history. 40

During the return passage on 15 June, IROQUOIS received a message from

CANFLAGLANT at sea in HMCS QUEBEC, indicating that should IROQUOIS

encounter the cruiser on passage an “attack” by torpedo was to be made. At 1930 a

white puff of smoke from QUEBEC was sighted at a radar range of 23.5 miles. Speed

was increased to 28 knots and the Generals repaired to the upper deck to watch the

fun.

“With the flag of G.O.C. flying at the fore, IROQUOIS

went into attack, being bracketed by star shell as she

did so. Torpedoes were ‘fired’ at a range of 3000

yards and had not IROQUOIS already been declared

‘sunk’ by Canflaglant, I feel sure that the attack would

have been successful.” 41

On arrival back at Halifax the destroyer was ammunitioned in preparation for her

return to the Far East to relieve HMC Destroyer CRUSADER. She set sail on 1 July

1954.

Four days after her arrival at Sasebo, 22 August, IROQUOIS was sailed for

Paengyong Do where Commander Oliver assumed the duties of CTG 95.1.2.

IROQUOIS’ first mission in the operational area was the rescue of a Korean fisherman

sighted on the morning of 27 August hanging on to a piece of wreckage from his craft

demolished during the previous day’s storm. Seven others of his crew had perished.

The Tribal’s third tour of duty in the Korean theatre followed a pattern similar to

her previous ones, although the weather seemed bent on exceeding itself in the number

and velocity of typhoons for which the area is renowned. Between September and

November 1954, IROQUOIS tangled with “June”, “Kathie”, “Lorna”, “Marie”, “Pamela”,

and “Ruby” – a succession of “femmes fatales” calculated to make even a seasoned

sailor’s hair stand on end.

When the fighting in Korea ceased, one of the urgent problems which gripped the

sympathy of many was the plight of the civilian population who inherited the tragic

aftermath of war. While the problem was handled on a large scale by the United

Nations Korean Relief Fund, most Canadian destroyers chose to express their concern

on a more personal level. On 1 December, as the first snowfall of winter swept in on

blustery winds from the north, the Commanding Officer of IROQUOIS with one of his

officers put ashore for Sochang Do, a barren island off the west coast of Korea, with a

large bundle of clothing donated by the ship’s company and purchased in Hong Kong.

In Korea, it is also customary to exchange gifts during the Christmas season, and the

villagers were eager to express their gratitude. Four live hens were proudly presented

to IROQUOIS’ company. “Oddly enough”, commented IROQUOIS’ captain, ‘the men

would have nothing to do with either killing them or eating them, so the Wardroom took

over and found them, cooked Chinese style, quite tasty.”

On 2 December on the arrival of the Netherlands frigate Van Zijll in the area,

IROQUOIS in company with HMCS HURON, weighed and proceeded from the Korean

islands for the last time. Both destroyers shaped course for Okinawa where they

participated in large-scale “Hunter-Killer” exercises with the American carrier Princeton,

seven US destroyers and the US Submarine Carp. At the conclusion of the very

valuable training exercise, a plaque, mounted with the badges of HURON and

IROQUOIS, was presented to the Rear-Admiral W. F. Rodee, USN, aboard Princeton.

After a pleasant Christmas Day spent at Sasebo, IROQUOIS departed the

following day for the passage home, a long and colourful voyage which included visits to

Colombo, Cochin, Bombay, Karachi and the gallant island of Malta in the

Mediterranean.

IROQUOIS, in company with HURON, arrived off Halifax in the morning of 19

March 1955 and was met in the harbour approaches by the Flag Officer Atlantic Coast,

Rear-Admiral R. E. S. Bidwell, in HSL 208, 42 who preceded the tribals into port. Once

alongside, the ship entered a five-week leave and maintenance period. Minor repairs to

the machinery were begun as well as a small amount of work on the hull. During the

period, fourteen days’ special leave, with added travelling time, was granted to each

watch.

IROQUOIS proceeded to Bermuda in May 1955. There, she was ordered to join

and escort HMC Destroyer NOOTKA who, while in collision with the South Breakwater,

Ireland Island, had damaged her bow. IROQUOIS floated four-by-four foot shoring to

her and remained with her until relieved by HMC Frigate TORONTO.

In May also there was a UNTD southern cruise. With cadets embarked for

training purposes, the cruisers QUEBEC and ONTARIO and the destroyers HURON

and IROQUOIS left Halifax on the 19 th . Visited during May and June were Fort Pond

Bay, Long Island; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Little Carrot

Bay, Tortola. A highlight in June was a night encounter exercise. Early one evening,

the group weighed and proceeded to take up strategic positions. QUEBEC then

attempted to break through the cluster of small islands in the vicinity of Tortola and

reach the island of St. Croix to establish a wireless station on one of the islands en

route. A “hide-and-go-seek” game developed, followed by a chase at twenty-five knots,

which ended in the theoretical torpedoing and destruction of QUEBEC.

A similar cruise in July 1955 took the ship to Cape Sable Island, Nova Scotia; St.

Andrew, New Brunswick; Eastport, Maine; and Argentia, Newfoundland. IROQUOIS

spent five days in the last-named port. On departing, she suffered a flash-back fire in

No. 2 Boiler Room due to the blowing out of two fire row tubes. The fire was soon

extinguished. The ship rejoined the group to visit Charlottetown, P.E.I.; Boston Mass.;

and Mahone Bay, N.S. before returning to Halifax.

On 8 August 1955, the First Canadian Destroyer Squadron was formed and

IROQUOIS became one of its members. However, because of her accident, only two of

her boilers could be steamed, and it was deemed unwise to sail her to take part in a

forthcoming NATO exercise. Because at the time 63% of her ship’s company had come

aboard within the previous three months and were hence in need of training, it seemed

to be fitting under the circumstances to ask permission to proceed on a “shake-down”

cruise to Bermuda. The request was granted.

The ship sailed on the 19 th . The next day a thick fog was followed by a violent

electrical storm. Large balls of St. Elmo’s fire formed at the tips of the whip aerials so

that the ship resembled a “Chinese procession”. The electrical storm was the precursor

of a gale which lasted for twenty-four hours. The wind blew from the south-west and

there were gusts up to seventy knots. A short and very heavy swell from the same

direction added to difficulties.

During the afternoon the wind, which had slowly veered, commenced to die

fitfully. The sea became confused. At 1637, a gigantic wave arose from the depths

alongside and broke over the starboard side. This wave was out of sequence with

those rolling toward the ship. It gave no warning. Catching the destroyer at the end of

a fifteen degree roll to starboard, it struck almost broadside on, forcing her over forty

degrees to port as measured by clinometer.

The chair on which the Commanding Officer sat, tipped over with the violent

movement of the ship, the legs broke and he fell on the top of the standard compass.

After he had got to his feet somewhat painfully, he found that the wave had sheared the

whaler’s davits off clean at deck level and that they and what remained of the whaler

were lying against the torpedo tubes. The wave had also stove in the starboard side of

No. 1 motor cutter and forced the griping pads through the port side. Minor damage

was suffered by the starboard No. 1 Boffin, the loading platform having been bent and

the cart-wheel sight crumpled like a sheet of paper. Other minor damage was incurred

in many places, there being twenty-nine work orders raised eventually upon hull items

alone.

This wave was later likened by Rear-Admiral Bidwell to the one which, in January

1943, smashed the bridge of HM Destroyer Roxborough and killed the Commanding

Officer, the First Lieutenant and a rating.

IROQUOIS had to cancel the voyage to Bermuda and turn back to Halifax. The

following month she was able to take part in the anti-submarine, “hunter-killer” exercise

known as “New Broom IV”. In October 1955, she began a refit.

On 19 December 1955, the First Canadian Escort Squadron was formed with

HMC Destroyer Escort ALGONQUIN becoming Senior Officer (CANCOMCORTRON 1)

and IROQUOIS a member. At the end of the month the ship joined other members to

secure alongside Jetty #5 in the Halifax Dockyard, but the Commanding Officer did not

think that IROQUIOIS’ appearance did credit to the rest, since she was still without

funnels and generally seemed to be suffering from “an advanced state of leprosy”.

On the 25 th of the following month, steam was finally got up in one of the boilers.

The ship got to sea on 16 February 1956. Trials showed up defects in newly installed

electronic equipment. She was making her way back to the Dockyard three days later,

when a storm came up. The wind blew steadily at fifty knots, gusting at about eighty.

Weakness now appeared in one section of the hull, and damage was caused to the new

asdic dome, the front panel of which was split horizontally in four places.

In March 1956, IROQUOIS steamed to southern waters, in the wake of other

members of the Squadron who had preceded her. She visited Trinidad, Barbados and

St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. In South-West Roads, St. Thomas, she took part in a

convoy exercise and an anti-raider action. The fleet of ships taking part was said to be

one of the largest operational RCN units assembled up to that time.

Following the exercises, San Juan, Puerto Rico; Miami, Florida; and Norfolk,

Virginia, were visited. Miami was found by the Commanding Officer to be “the best

leave port I have ever visited”. Its only disadvantage was its restricted harbour which

had only six wharves to cope with the heavy traffic.

On 22 May 1956, IROQUOIS steamed up the St. Lawrence River in company

with HAIDA and ALGONQUIN. While in Montreal in June the ship embarked some

seventy members of the Naval Officers’ Associations for a three-hour voyage along the

water-front. During the cruise, the ship was accompanied by millions of shad-flies,

“frantically annoying insects” which “made it next to impossible to speak on the bridge,

except in dire emergency, unless one were willing to spend some time cleaning them

out of one’s mouth”.

Quebec City was popular with the ship’s company and a wonderful reception was

found awaiting all in Trois-Rivieres. The Commanding Officer was told that this was the

first time the town had been visited by an RCN vessel. One of the town councillors

noted that “the last time the Iroquois visited Trois-Rivieres, two hundred people were

killed”. 43 From here, the ship went on to call at Sept-Iles, Quebec; Corner Brook,

Newfoundland; and Pictou, N.S.

Exercises followed during the summer months. On 19 September 1956, the ship

left with HURON and MICMAC on the first leg of a fall cruise to European ports. Ponta

Delgada in the Azores was the first landfall. Here they were boarded by two barbers

who cut hair at 50 cents the head at an average rate of speed of one customer each two

and a half minutes. The Commanding Officer’s position brought him special

consideration: his hair cut lasted for four minutes and at no extra charge. Observing

that the average daily wage in the Azores was calculated at something like 32 cents,

there was no doubt that the barbers must have left, temporarily at least, wealthy men.

The destroyers reached the Irish Sea and found it stormy. In Dublin Bay a pilot

boarded IROQUOIS in a full gale. Happily the city made up for the weather by a warm

welcome.

Moving northward in October 1956, the ships proceeded up the River Foyle to

Londonderry. During exercises out from this port on the 10 th , a Neptune aircraft was lost

with its entire crew of nine.

Bangor, Belfast and Southampton were visited. On 1 November 1956,

IROQUOIS and MICMAC detached from the First Canadian Escort Squadron with

whom they had been in company, to enter Lorient, France. After an interesting visit in