From its inception in 1910 as the Canadian Naval Service, until July, 1941, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) had a category of sailor known as “Boy.” He joined as young as age fourteen, though in later years admission was increased to age seventeen and one-half.

This designation was inherited from the Royal Navy (RN), where it was used as a recruitment device to attract boys, often from poorer homes or even orphanages, who were too young to meet the normal entry age of eighteen. The hope was that if recruited at such an early age, they would become attracted to naval life and eventually trained up to assume the responsibilities and skills of Petty Officers (POs) and Chief Petty Officers (Chiefs) in certain vital trades in the Seaman branch (Gunnery, Torpedoes) and Communications (Visual Signals and Wireless Telegraphy (WT) branch – sending messages via what we now refer to as radios – and to a much lesser degree, in the Supply (Writers, Storesmen) and Medical branches.

Canada’s Boy Seamen joined the first two cruisers RAINBOW (Esquimalt) and NIOBE (Halifax) in 1910 under a seven year engagement, though their “men’s time” did not commence until they turned eighteen, at which time they were advanced to the rank of Ordinary Seamen or the appropriate equivalent in Signals, WT, etc.

During the hostilities of 1914-1918 the training of Boys in the cruisers on either coast was limited, and any boy approaching the RCN to enlist as a Boy was given only one option, the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve (RNCVR).

The RN was fighting a submarine war off its coasts, and desperately needed Boys in the Seaman branch – “Men of Good Character and Physique” – who were sixteen years of age or older. Canadian boys jumped at the chance to defend the British Empire though, in fact, many would stay in Canada and in smaller Canadian ships, even if others were able to go to the RN and service in whalers, anti-minesweeping and anti-submarine trawlers and a host of other patrol vessels. Most served in British waters but some went as far as the West African coast where they performed patrol and escort duties.

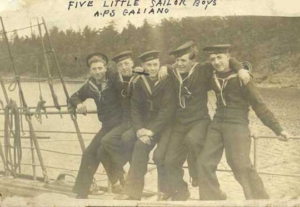

At home, four Boys were lost out of a crew of thirty-eight when, in October, 1918, HMCS GALIANO, a patrol vessel, disappeared during a severe storm in Queen Charlotte Sound.

“Five little sailor boys” of the patrol ship GALIANO, which disappeared in Queen Charlotte Sound. Photo Catalogue No. VR992.84.14.

In all, 422 men of the Canadian naval forces would die on active service between 1914 and 1918. GALIANO was the only vessel lost.

Both Boys and the RCN survived the harsh budget cuts of the early 1920s, but the training for gunnery, torpedoes, visual signals and wireless were carried out almost exclusively in the United Kingdom (UK) at shore establishments and was followed by further training in training ships in the Home Fleet. The RCN was expected to function as an arm of the RN, so training in these four key trades had to be carried out in a big fleet situation. Most of the advanced training for those who were already eighteen and already in their trades was also carried out in the UK.

After his training with the Home Fleet, the Boy would have turned eighteen, rated as “trained”, promoted and thus been ready to rejoin the RCN. By the late 1930s Boys were serving in the usual battleships and cruisers, but increasingly in destroyers and the new generation of RN aircraft carriers.

In the pre-war years boys had joined as Boys for adventure, travel and to learn a trade with an eye to having a career with the RCN, but with the outbreak of war in 1939 motivations began to change. Now it was more and more a case of joining to fight in a war, and when it was over to get on with other things. This undermined the key reason for having Boys: training them up to be POs and Chiefs, or even commissioned officers.

Furthermore, the RCN was recruiting Ordinary Seamen at age seventeen and one-half, like Boys, and training them in an identical fashion as they waited for them to turn eighteen, thereby placing them beyond the legal prohibition against having underage sailors at sea in war time. Ordinary Seamen had no prohibitions on smoking, no shorter leave periods, no earlier bed times and other petty restrictions, but there the differences stopped. The Boys’ programme no longer seemed to make sense – though it would be kept in the RN until the mid-1950s – and in mid-1941 it was discontinued.

Although the rank of Boy disappeared, their impact did not. They helped see the RCN through some of its toughest times, the Second World War, the Korean War and the Cold War. The last of the former Boys left the RCN in the late sixties and the early seventies as POs, Chiefs and Commissioned Officers in specialist areas, and like the Boys before them they gifted the RCN with a rich legacy of dedication and service.

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum