AN OFFICIAL HISTORY OF

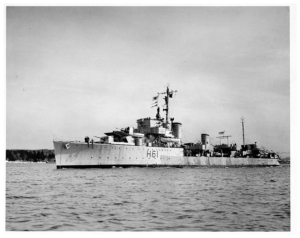

HMS Express, pennants H-61, was built on the Tyne by Swan Hunter and engined by the Wallsend Slipway. She was laid down on 24 March, 1933, launched on 29 May, 1934 and commissioned on 2 November of the same year. She served in the Fifth Destroyer Flotilla with the Home Fleet until 1939.

Just before war broke out, she had been fitted for mine-laying and on 9 September, 1939, she and HMS Esk, a sister ship, laid the first British offensive mine field of the war in the Heligoland Bight. On another mine-laying operation off the Dutch coast on 31 August, 1940, she, Esk and Ivanhoe all struck German mines before they could lay their own. Express was severely damaged and was towed back to the Humber for repairs, but the other two destroyers were sunk.

In commission again the following year, she joined the Eastern Fleet on its formation. She was among the destroyers escorting HM Ships Prince of Wales and Repulse when they sailed from Singapore on 8 December, 1941. When the two heavy ships were sunk on the 10th, Express went alongside the slowly capsizing Prince of Wales and took off most of her crew dry-shod, staying until the last possible moment. As the ship went over, her bilge keel fouled Express’, lifting her and damaging her slightly – she had to go full astern on her engines to get clear.

In late 1942 the Canadian cabinet asked Britain for the loan of eight destroyers to reinforce the escort groups on the North Atlantic convoy routes. The Admiralty responded with the gift of six of which Express was one. They had already begun to refit her for escort duties and it only remained to rename her GATINEAU after the river flowing into the Ottawa and to provide her with a Canadian crew. The river, in turn, took its name from a French fur trader and civic official, Nicholas Gatineau, who developed it as a trade route that took him around Iroquois territory safely to the Hurons’ hunting grounds. He disappeared in 1683 – according to rumour he was drowned in the river.

HMCS GATINEAU was commissioned into the Canadian fleet on 3 June, 1943, and sailed from the United Kingdom on 2 July as Senior Officer of Escort Group C-2 escorting Convoy ON-191. She quickly settled into the routine of the “Newfie-Derry run” – the work of the Mid-Ocean Escort Force plying between St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Londonderry in Northern Ireland. The U-boats, badly beaten early in the year, stayed away from the North Atlantic convoys until September. GATINEAU sailed on 15 September in charge of the escort of ON-202 which, in company with ONS-18, was beset by twenty-one U-boats. Of particular importance in this convoy battle is the fact that this “wolf-pack” was armed with acoustic torpedoes (called GNATS by the Allies) for use against escort vessels. The U-boats made contact with the convoy on the evening of the 19th and the running fight continued for five days and nights into the early morning of the 24th. HMS Lagan was the first to become a casualty to the GNAT when she was damaged at 0303 on the morning of 20 September, but U-341 had already been sunk by an aircraft.

HMCS ST. CROIX (one of the ex-American “four-stacker” destroyers) and HMS Polyanthus, corvette, were sunk the same evening.1 Meanwhile U-338 had been accounted for by another aircraft. On 22 September, HMS Keppel sank U-229 and the same night HMS Itchen was sunk taking to the bottom all but two of her own ship’s company, all but one of the survivors from ST. CROIX and the only man picked up from Polyanthus. Also sunk in the action were six merchant ships so that the final score was three U-boats sunk for a loss of three escort vessels sunk and one damaged and six merchantmen sunk.

The U-boats found their new weapon no great advantage – they had got a bloody nose using it and on the day Itchen was sunk, barely two days after its first use on Lagan, the Admiralty made a signal giving instructions for effective counter-measures.

GATINEAU had been slightly damaged by her own depth-charges in the action and had to be hauled out at Bay Bulls for repairs to her stern glands. Then, in mid-November, after four more passages across the Atlantic, she was sent to Halifax dockyard to be fitted with heating apparatus to make her more comfortable for her crew in winter. This was her first visit to a Canadian port since Newfoundland was a crown colony at that time.

She rejoined C-2 group, but was no longer Senior Officer, and after an east-bound convoy she found the group allocated to “Support” duties. This meant it joined a convoy in addition to its close escort and gave extra protection through the more dangerous parts of its passage. They sometimes spent even longer at sea at a stretch because the ships would sail from Londonderry (where C-2 was based) with a west-bound convoy, accompany it for about two-days, transfer to an east-bound convoy for a day, then to a west-bound again and so on, fuelling from tankers in the convoys as it became necessary.

The Senior Officer of a Support Group had greater freedom of action than he would if he were in command of the close escort because he could leave the convoy, if there were no immediate danger, to follow a promising scent. Just such a case occurred in March, 1944 when GATINEAU made contact with a U-boat while supporting Convoy HX-280. This led to a “hunt to exhaustion” which lasted from 1000 on 5 March to 1830 on the 6th. GATINEAU herself had to leave the hunt during the night because she was short of boiler feed-water, but her contact led to the sinking of U-744 by the other ships of the group. Even after having about two hundred depth-charges and three patterns each from squid and hedgehog dropped on her, the U-boat was little damaged and was prepared to fight it out with her guns when she broke surface, but she expected to find only two escorts waiting for her. As it was she was deluged with shell from five ships and never got a man to her guns. She surrendered almost at once. It was only her air supply that had been exhausted.2

At the end of April, 1944, GATINEAU, along with the other destroyers in the Mid-Ocean Escort Force, was withdrawn from the Atlantic. She was allocated to Escort Group No. 11, consisting entirely of Canadian “River” Class destroyers, for duty in the English Channel for the landings on the Norman coast. The work was mostly patrolling the supply lines to protect them against submarines. HMC Ships OTTAWA (Senior Officer) and KOOTENAY and HMS Statice distinguished themselves by sinking a U-boat on 7 July, but GATINEAU was elsewhere at the time. Just a few days later her boilers blew several tubes and it was decided to send her home for a refit. This kept her in Halifax from August, 1944 to February, 1945, and it was 1 May, a week before VE-Day, before she was ready to sail again from Londonderry for operations with EG-11.

During that week she carried out patrols in the channel. On 12 May the group carried out Operation “Nestegg” the reoccupation of the Channel Islands. They escorted the transports that landed British troops on the islands and carried out patrols off shore afterwards. It was not clear yet whether all U-boats had heard of the end of hostilities so EG-11 had more patrols and two channel convoys to escort before they sailed northward for Londonderry on 23 May. On the 30th they called at Greenock, picked up homeward-bound Canadian naval personnel and sailed for home. On 6 June they arrived in Halifax and EG-11 was disbanded.

GATINEAU’s first peace-time duty was to act as transport – she paid another call to Greenock to bring Canadians home taking from 22 June to 10 July for the two-way passage. Then she was allocated to HMCS ROYAL ROADS, the Royal Canadian Naval College, for sea-training duties, and sailed for the west coast on 11 August, 1945, arriving 5 September at Esquimalt. She commenced a refit for training work but before it was complete HMCS CRESCENT, a more modern ship, became available and GATINEAU was paid off on 10 January, 1946.

In March 1947, when the fleet was being reduced, GATINEAU was declared surplus and later the same year she was sold and broken up.

Footnotes

- The new ST. CROIX is a sister ship to the new GATINEAU.

- Seven ships were engaged in this action: they were HMC Ships ST. CATHARINES, CHILLIWACK, GATINEAU, FENNEL and CHAUDIERE, and HM Ships Icarus and Kenilworth Castle.

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum