BRIEF HISTORY OF

Caution: This article contains dated, biased and/or racist language.

Among ships, as among men, there from time to time emerges one upon whom the gods seem to have smiled. Good fortune is their handmaiden in adventure, an aura of distinction pervades their every endeavour, success crowns their achievements. Such a ship is Her Majesty’s Canadian Destroyer HAIDA, whose record in two wars has won her an honoured place in Canada’s naval history.

HAIDA was the fourth [1] Tribal to join the Royal Canadian Navy. Launched at Newcastle, England, 25 August, 1942, the destroyer was sponsored by the Canadian-born Lady Laurie, Lady Mayoress of London [2]. Ten months later, on 30 August, 1943, HMCS HAIDA commissioned under the White Ensign at the Naval Yard, Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd, Walker-on-Tyne. Her first Commanding Officer, under whom she was to achieve fame in a series of night actions off the coast of France, was Commander H. G. DeWolf, RCN.

Structural weaknesses in the RCN’s modified Tribal design, which had shown up shortly after IROQUOIS and ATHABASKAN went to sea, were corrected in the two Tribals then under construction in the United Kingdom. Both HAIDA and HURON had their upper decks stiffened while they were still on the slips, thus saving their future ships’ companies many months of distress and frustration which was the unhappy lot of their pioneer sisters.

On 17 September 1943, while carrying out her trials, HAIDA received a visit from Mr. Vincent Massey, then High Commissioner for Canada in the United Kingdom, who walked around the ship, stopping to chat with many of the men at their work. The following day, all-power and acceptance trials completed, HAIDA disembarked her trials party at Methil in the Firth of Forth and shaped course for the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet base at Scapa Flow. Here she joined the 17th Destroyer Flotilla. Working up exercises, in particularly foul weather, occupied the destroyer throughout the next four weeks.

HAIDA’s first operational assignment followed immediately. From 14 to 22 October she was designated Senior Officer of a destroyer group [3] ordered to sea as part of the covering force for operations “F.Q.” and “F.R.” These operations – the first of which was a relief expedition to the garrison on Spitzbergen; the latter, the passage of a number of Russian minesweepers and small anti-submarine vessels to Murmansk – were timed to coincide so that the same heavy covering force would be at sea to protect both operations simultaneously.

Upon return to Scapa, HAIDA was dispatched, 25 October, to Cape Wrath to rendezvous with HMS Formidable and escort her back to Scapa where the fleet carrier was required for the forthcoming Home Fleet operation, “F.S.” HAIDA joined in this operation as part of the destroyer screen for the heavy battle units ordered to sea to ensure the safe arrival of convoy RA-54A [4] and to lure, if possible, the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst out of her hiding place on the Norwegian coast. The entire operation, however, passed without encountering the enemy and the safe arrival of the thirteen merchant ships augered well for the season’s series of North Russian convoys.

In her next Home Fleet assignment, operation “F.T.”, HAIDA with her sister Tribals HURON and IROQUOIS, formed part of the destroyer flotilla under HMS Onslow dispatched to escort convoy JW-54A to Russia. The convoy, carrying valuable cargo for the hard-pressed Russian battlefront left Loch Ewe on 15 November. While its progress was impeded by a northwesterly gale, and enemy submarines were known to be in the vicinity, all ships arrived safely [5]. The return journey with RA-54B was equally uneventful.

On December twenty-fifth, 1943, four Canadian Tribals were at sea escorting convoys [6] on the “Murmansk Run”. There was little or none of the traditional festive spirit in the air; in his report for the month HAIDA’s Commanding Officer entered the following melancholy item:

“Christmas Day was spent at sea under unusual conditions – in the Arctic, in bad weather and almost constant darkness escorting a straggling convoy, shadowed and reported by enemy aircraft with the Scharnhorst and an unknown number of U-boats in the vicinity.”

However, as events in the next twenty-four hours moved to their dramatic climax, it was the enemy who was to have most cause for gloomy reflections. For, contrary to the expectations of Grand Admiral Doenitz, Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, who reasoned that since two convoys had already passed unmolested the enemy would be less prepared for trouble, a heavy British battle fleet had put to sea to reinforce the passage of north-bound JW-55B and home-bound RA-55A. The suspicions of the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet, wearing his flag in the battleship HMS Duke of York, had been aroused by the very ruse which the enemy had employed to trap them. On 23 December Force 1, comprising the RN Cruisers Belfast [7], Norfolk (who had stalked the Bismarck to her doom) and Sheffield, had hastened down the Norwegian coast from Kola Inlet in the event the Scharnhorst might be tempted to come out. At 2300 on the same day, Force 2 [8], steamed out of Akureyri, Iceland, ready to do battle if the German raider should put to sea.

Scharnhorst, blithely unaware that any capital ships were in the area, had departed Altenfiord at 1900 on 25 December, escorted by the German 4th Destroyer Flotilla. It was to be her last sortie into the North Atlantic.

Twice the Nazi battle cruiser had attempted to close convoy JW-55B and twice was driven off by the accurate gun-fire of the British cruisers in Force 1. From their station as close escort for the merchant ships, the Canadian Tribals watched with growing concern the glow of the fireworks over the horizon. At this point, HMS Onslow, senior officer of the convoy escort, passed the code word “Strike” – the order for the destroyers to form up on their divisional leaders in readiness for a torpedo attack. Shortly afterwards, when the Scharnhorst retired, this order was cancelled. Despite the fact that the German battle cruiser possessed fire power far superior to the British cruisers present, (who endeavoured to hold Scharnhorst until the Duke of York, hurrying up from the southwest, could engage her) the Nazi warship chose to rely on her superior speed and fled. Not, however, that the Scharnhorst was in any way lacking in gallantry. As Germany’s only capital ship in northern waters in operational readiness, she was under orders not to risk destruction in a duel with heavy ships [9]. When the superior guns of the Duke of York finally caught and crippled her, Scharnhorst went down [10], with her colours flying and all guns that had not been disabled still firing.

The convoy meanwhile proceeded on its way, constantly shadowed by German U-boats and aircraft. HAIDA’s guns opened fire to drive off the marauding planes and her depth-charges succeeded in keeping the underwater foe at a distance. The merchant ships were all brought safely into Kola Inlet on 29 December.

By comparison, the return voyage with RA-55B was uneventful. HAIDA carried out an A/S attack on 3 January, but a twenty-minute search in company with HURON failed to produce any positive results. The destroyers were detached from the convoy at noon on the 7th and arrived at Scapa the same evening.

After a brief period in harbour, HAIDA and IROQUOIS were sailed on 10 January 1944 for Plymouth where they were to operate under the Plymouth Command.

The opening of the year 1944 witnessed a marked change in Allied naval strategy in the English Channel area. The forces at sea were moving over from the enforced defensive role imposed upon them during the dark early years of the war to the grand offensive sweep which climaxed in the summer of 1944 with the successful invasion of Europe. Defeat, perhaps for the first time, became a real and ugly possibility for the German High Command as they watched Allied destroyer flotillas boldly moving into the confined waters off the French coast which the Nazis heretofore regarded as their own.

The determined Allied policy to throttle the enemy’s coast-wise shipping and bottle up her harbours, through a heavy programme of minelaying, got underway in January. The code names for these anti-shipping and minelaying strikes were known (respectively) as operations “Tunnel” and “Hostile”. Before the invasion of Normandy got underway at the beginning of June, 1944, HAIDA had chalked up ten “Tunnel” and nine “Hostile” operations.

HAIDA had taken part in two of these “Tunnel” operations [11] before she was temporarily recalled to Scapa to take part in operation “Posthorn”. HAIDA, IROQUOIS and ATHABASKAN sailed in company from Plymouth on 4 February and arrived at the windswept northern anchorage towards midnight on the 5th.

“Posthorn” was planned as an air strike from the carrier HMS Furious against enemy shipping in the shoal-studded waters between Stadlandet and Ytteröerne on the Norwegian coast. The German coast-wise traffic off Norway was of large importance to the enemy’s hold on the northern area of that country for it was the primary means of communication with the remote Nazi garrisons stationed there. The three Canadian Tribals were required to form part of the destroyer screen for the heavy support force involved: the battleships HMS Anson and FS Richelieu and the RN Cruisers Belfast and Nigeria. [12]

The hunt for enemy shipping, however, proved disappointing and, no worthwhile targets being encountered by the aircraft, an attack was carried out on an alternative objective, the beached SS Emsland. A merchant ship of 5,200 tons, the Emsland had been damaged earlier by aircraft of the Coastal Command and was now undergoing repairs. An attack was successfully carried out and the battle force returned to Scapa on 12 February. None of the surface ships saw any action throughout this operation.

On their return to Plymouth, 15 February, the three RCN Tribals together with HM Ships Tartar (S.O.) and Ashanti were formed into the 10th Destroyer Flotilla . [13] Three days later, when IROQUOIS departed for refit in Canada, HURON replaced her, joining from Scapa on 18 February. A heavy programme of exercises and operations now faced all ships in United Kingdom waters. Operation “Neptune” [14] was less than four months away and a rigorous programme of training characterized this crucial period of preparation – the prelude to invasion.

HAIDA, in company with other ships of her group, carried out a strenuous round of exercises. The high level of efficiency which the 10th Destroyer Flotilla later achieved as a night fighting unit was accomplished as a result of many exacting hours of group practice in manoeuvring, night encounter exercises and radar tracking.

In addition to these exercises designed to increase group efficiency, HAIDA also participated in a number of pre-invasion rehearsals in which the assault forces committed to the invasion of Normandy were practising their carefully prescribed roles.

HAIDA’s operations in these exercises were of two varieties: patrol duty off the practise area to forestall any attempt by the enemy to attack the assault craft, and bombardment duties in support of the assaulting forces. In Exercise “Fox” (11-12 March) and Exercise “Muskrat II” (24-25 March), HAIDA was allocated to the screening force on patrol in the outer area of the assault exercise. On the 30th March HAIDA took part in Exercise “Beaver”. The destroyer formed part of the Gunfire Support Force together with HMS Glasgow (S.O.), Black Prince, Tanatside and Brissenden and her sister Tribal HURON.

One of the first large-scale combined assault exercises – “Trousers” – took place east of the Needles on 12 April. The whole available Eastern Task Force and some of the Western Task Force ships took part. HAIDA and HURON under HMS Tartar formed part of the screen which was stationed out in the Channel parallel to the coast.

For three months Canadian Tribals in the Channel and Bay of Biscay had sought the enemy, but it was not until the night of 25/26 April while engaged on one of the “Tunnel’ missions against Nazi coastal shipping that the fruits of long hours of practise manoeuvre and uneventful patrol were harvested.

The ships of Force 26 [15] passed Plymouth gate outward-bound at 2105, 25 April. A dark, moonless sky dotted with stars, clear weather, and an unruffled sea set the stage for the action-filled engagement which filled the hours before the dawn. The Force steamed in towards the French coast in battle formation: HAIDA and ATHABASKAN forming the 2nd Sub-Division disposed one and a half miles, 40 degrees, on Ashanti ’s starboard bow; HURON and Ashanti in the 3rd Sub-Division stationed in relative position on the cruiser’s port bow.

Aerial reconnaissance and Naval Intelligence sources had established the presence of three “Elbing” Class destroyers at Saint Malo on 23 April. In addition, four Torpedo Boats and some twenty “E” or “R” boats were known to be at Cherbourg. In the hope of encountering some of these enemy forces, Force 26 was to steam to within ten miles of a position off Ile de Vierge, patrol in an east-north-easterly direction (roughly on a course for Saint Malo) and, if the enemy was not encountered, navigate so as to be within twenty-miles of the English coast by dawn.

At 0125 on the 26th, while still some eighteen miles from the French coast, an enemy shore battery opened its guns on the Force, firing ten salvoes at the ships during the next half hour. Although none of the shells fell anywhere in the vicinity of Force 26, it was obvious that an enemy shore radar station had located them and hope of an engagement with enemy surface forces faded. Five minutes after the battery had opened fire, Force 26 reached its patrol position and course was altered to 070° at twenty knots. Half an hour later, at 0200, Black Prince picked up a radar contact, bearing straight ahead, at 21,000 yards. Two minutes later this was confirmed in HAIDA. At 0205 Black Prince signalled the Commander-in-Chief Plymouth stating that the Force was in contact with four enemy ships [16] bearing 081 degrees at seven miles. The enemy at this point became aware of the Force’s presence, and quickly altered to port 180 degrees. [17] A stern chase ensued and at 0220 the cruiser opened fire with star-shell. [18] The enemy immediately made smoke, attempting to clear the area at speed. Five minutes later HAIDA and ATHABASKAN opened fire at 10,900 yards, and Black Prince joined in with “A” turret while her “B” turret continued to fire star-shell. Within ten minutes, two of the enemy ships were observed to be on fire. Unfortunately, at 0248 the guns of the cruiser’s “B” turret failed and the attacking forces were temporarily robbed of illumination. Shortly afterwards a torpedo was seen approaching on the starboard beam, about two cables distant. A signal from Ashanti gave warning that more torpedoes had been fired, so Black Prince, her “B” turret still out of action, hauled off to seaward until 0307.

Meanwhile the Tribals had continued the chase to the eastward. The range decreased steadily and by 0313, with the enemy less than 5,300 yards away, HAIDA altered course to port to open “A” arcs. Several hits were observed to fall on the enemy. At 0325 HAIDA sighted one of the Elbings attempting to break away to the westward. Together with ATHABASKAN, she altered course to engage her, leaving Ashanti and HURON to continue the chase to the eastward.

The following excerpt from HAIDA’s report of the action gives a graphic account of the final moments of the engagement:

“At 0327 radar range was 4000 yards ahead and course was altered to port to open “A” arcs and illuminate with “X” gun. The first starshell fell in line and the first salvo hit and started a fire. Successive salvoes each produced hits and within a few minutes the enemy was on fire throughout. ATHABASKAN had joined in as soon as she had cleared her line of fire. The target was identified as an Elbing Class destroyer.”

“The enemy at first returned our fire but by 0332 he was stopped, on fire and apparently out of action. Course was altered towards and torpedoes were fired at a range of less than 1000 yards. Two were observed to run straight for the target and two to miss ahead but no hits were obtained. The enemy was engaged with close range weapons at this time, and the fire appeared to be very effective. HAIDA then led round and again passed at less than 1000 yards range and attempted to sink the target by gunfire. The enemy came to life at this stage and put up a spirited close range fire, in spite of the fact that the ship appeared quite inhabitable….”

“By 0340 the enemy was literally a blazing wreck, but was still on an even keel and showed no sign of sinking. HAIDA withdrew to the northward to allow the 3rd Sub-Division [Ashanti and HURON] to fire torpedoes, then closed once more followed by ATHABASKAN for a final go from 2000 yards. Each hit increased the fires which now burned with an intense white heat accompanied by frequent explosions. The ship began to list to port and settle at about 0400 and destroyers started to withdraw. The enemy finally sank at 0421.”

Of the three enemy destroyers known to be present, one had been sunk [19], the others though damaged, made good their escape. It was a creditable night’s shooting and the foretaste of even greater successes to come.

As the ships approached Plymouth at dawn on the 26th, Black Prince signalled the destroyers:

“Force 26 will wear battle ensigns on entering harbour.”

With the White Ensign fluttering from the yardarm, the ships passed Plymouth gate at 0821. Steaming up harbour, the Force was the object of widespread interest. Ship after ship saluted them as they passed. For the Canadian destroyers present it was a particularly proud and historic occasion; it marked the first time RCN ships had sunk an enemy destroyer in surface action.

That evening, 26-27 April, a large-scale amphibious exercise – “Tiger” – was to get underway off Slapton Sands on the Channel coast and every seaworthy destroyer that could be spared from the Plymouth Command was required to patrol to seaward of the landing craft. HAIDA’s company, dog-tired after their night at action-stations and a hard day’s labour ammunitioning ship and cleaning up the debris caused during the previous engagement, prayed for a quiet night as they sped out past Plymouth sea-gate and headed for their patrol position, in company with ATHABASKAN. [20]

Throughout the night, action stations was sounded on three occasions, but no activity developed in the sector where the Canadian Tribals were screening the operation. The presence of E-boats [21] in the vicinity was suspected but HAIDA made no contact with them. The following night, however, when HAIDA was detached for duty off the French coast, one of the follow-up convoys for the “assault” was attacked by E-boats and there was an unfortunate loss of life in the sinking of two LST’s (Landing Ships Tank). Later, the German radio had simply announced that ships of a channel convoy had been torpedoed and sunk. Apparently the German Command was unaware that these vessels were “invasion” assault craft and not the usual merchant ships in convoy.

On the night of 28/29 April, a mine-laying operation was to take place off Ile de Bas, north-west coast of France. The operation, known as “Hostile XXVI”, was to be carried out by a force of eight Motor Launches and two MTB’s (Motor Torpedo Boats). The presence of two enemy destroyers of the “Elbing” Class had been discovered off St. Malo and in order to forestall any interference by them with the minelaying operation, HAIDA and ATHABASKAN were ordered to form a covering force to seaward.

At 2000 on the 28th, the mine-laying force left Plymouth and at 2215 HAIDA (Senior Officer) and ATHABASKAN followed in line ahead. A clear sky, lit by moon and stars, bathed the destroyers in a misty light as they knifed their way through the smooth waters of the Channel and headed for the French coast. The mine field was to be laid roughly ten miles north-east of Ile de Bas and the Tribals were to patrol to seaward of the mine-laying force, carrying out an “east and west” patrol approximately twenty-three miles north-northwest of Ile de Bas.

At 0300 on the 29th, the destroyers had reached their patrol position and were steaming at sixteen knots on a mean course 260°. Between 0010 and 0130 plots had been received in the Area Combined Headquarters, Plymouth, of vessels proceeding to the westward at twenty knots between St. Malo and Roches Douvres. These enemy ships it was later revealed, were the German destroyers T-27 and T-24, both of which had been damaged in the Channel action three nights earlier. The Nazi warships were bound from St. Malo to Brest for repairs. [22]

At 0258 these enemy vessels were again detected by radar which revealed them to be at this time north-east of Morlaix and continuing to the westward. At 0307 HAIDA and ATHABASKAN were ordered to proceed to the south-west with all dispatch. The Tribals altered course to 225° steaming at maximum speed to intercept the enemy.

At 0332, course was adjusted to 205° and at 0343 to 180°. At approximately 0400, ATHABASKAN obtained a radar contact bearing 133°, fourteen miles. This was confirmed by HAIDA immediately afterwards, the enemy’s speed and course being estimated at twenty-four knots 280°. HAIDA altered course to 160° at 0400 and to 170° at 0408, the bearing of the enemy remaining steady at about 125°. The two forces were thus closing at a 90° track angle on a roughly steady bearing. [23]

At 0412, with the range down to 7,300 yards, HAIDA gave the order to “engage the enemy” and opened fire with star-shell. Two minutes later two “Elbing” destroyers were sighted bearing 115°. The German ships, under instructions to “head towards the coast and avoid combat”, [24] swung away to the southward, making smoke and firing torpedoes as they turned. A spread of six torpedoes was launched by T-27, but all of these ran in the wrong direction, greatly endangering her companion, T-24. The latter, while turning away, also attacked with torpedoes, three of these also running in the wrong direction.

Unluckily, one found its mark.

At 0417 the Canadian destroyers altered 30° to port to comb possible torpedo tracks, while at the same time keeping “A” arcs open. Seconds later one of the enemy torpedoes found its mark in ATHABASKAN. Badly damaged aft, where a large fire immediately broke out, the destroyer lost way and, swinging round to port, came to a standstill.

The enemy made off on a south-easterly course, hammered by gun-fire from HAIDA who at the same time was laying a smoke screen for the crippled ATHABASKAN. HAIDA obtained her first hit at 0418. Four minutes later the enemy force split; T-24, having already sustained several hits, broke away to the eastward, while T-27 made a dash for the French coast. HAIDA took after her in hot pursuit.

At 0427, from out of the billowing clouds of steam and smoke astern, there was a shattering explosion and a great column of fire shot into the night sky. HAIDA’s men looked back to watch with horror and incalculable sorrow as the blazing wreckage of ATHABASKAN upended slowly in the water and then slid swiftly under.

Grimly determined to avenge the fate of her sister ship, HAIDA’s guns struck out at the enemy, scoring hits. At 0435, T-27, clearly visible in the light of the fires which had broken out aboard her, was seen to be aground on a reef off Pontusval, north-west coast of France. Another German destroyer would fight no more. [25] Contact with T-24 having been lost [26] and with daylight not far off, HAIDA’s Commanding Officer ordered course set to pass through the position where ATHABASKAN had blown up and preparations were made to pick up survivors.

Fifteen minutes later the destroyer stopped amidst a large group of survivors who were milling around in the oily water. Scramble nets were flung over the side and all floats and boats lowered. Throughout the next tense eighteen minutes, HAIDA lay five minutes off the enemy-held shore, well within range of coastal guns, while 42 survivors were hauled on board. Then, with dawn approaching and urged by ATHABASKAN’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Commander J. H. Stubbs, DSO, RCN, to get away while there was still time, HAIDA shaped course for Plymouth. Before German minesweepers arrived in the morning to take eighty-five of ATHABASKAN’s company prisoners-of-war, her gallant Commanding Officer and 127 of his crew had perished.

HAIDA passed Plymouth gate inbound at 0840 on the 29th, once again flying her battle ensign at the yardarm; but this time victory had not been without cost. She moved slowly up harbour, without the familiar outline of the ATHABASKAN astern, as ship after ship saluted her.

The destroyer bore many marks of her fight with the enemy, and, once at anchor, her ship’s company faced the relentless demands of the moment. HAIDA had to be made ship-shape again and the heavy, back-breaking job of re-ammunitioning had to be carried out, in spite of fatigue, in spite of sorrow. But HAIDA was not without friends. When her men turned out for duty they found that a volunteer party from HMCS HURON already had the work well in hand and insisted upon finishing the job.

Meanwhile, far out in the English Channel another chapter of heroism and achievement was being written by a plucky trio from HAIDA who had manned the destroyer’s motor cutter when it was sent away to aid in the rescue of ATHABASKAN’s survivors. Their original intention had been to tow the various Carley Floats toward HAIDA and thus speed rescue operations. However, when HAIDA had to clear the area before rescue operations were complete, the three seamen were left to their own resources, to save those they could and escape, if they were lucky, across the 100-mile stretch of seaway that separated them from England. Chased by one of the German minesweepers who came out from Brest with the first light of day, bedeviled by a temperamental engine that conked out on several critical occasions, and buzzed by German Messerschmidts, the volunteer crew nonetheless succeeded in saving the lives of six more men from ATHABASKAN and two from HAIDA who had been swept away from the scramble nets when HAIDA shaped course for Plymouth.

Towards evening on the 29th, the motor boat was spotted by Spitfires of the Royal Air Force who stayed overhead until 2200 when an Air-Sea Rescue Launch came alongside and took off the exhausted survivors. Given warm clothing and food and a hot noggin of rum, the men were then sped into Penzance where they were taken at once to a West Cornwall hospital. After a night of rest, HAIDA’s men were returned to their ship.

May 1944 was another busy month for HAIDA. After a few days in harbour to make good her action damage, HAIDA put to sea, 4 May, to take part in the bombardment and patrol exercises in operation “Fabius I” – one of the final full-scale invasion rehearsals. D-Day now loomed a scant month away. Three more “Hostile” operations in support of mine-laying activities were carried out during May, while a series of practice exercises brought the ship’s company to the high state of readiness required for the critical weeks ahead.

On the momentous night of 5/6 June, 1944, HAIDA’s men, restless for a more active role, had to content themselves with a quiet patrol north of the Channel Isles, while the vast air armada of transports and gliders, travelling just a few hundred feet overhead, moved endlessly into the night, on their way to open the invasion. HAIDA’s role in operation “Neptune” [27] was the protection of convoy lanes leading to the Normandy beach-head and to forestall any concerted Nazi attempt to break through the outer defence screen. It was not the kind of aggressive action her men had come to expect and excel in, but the destroyer was seen to find a task more to her liking.

Photographic reconnaissance of the port of Brest had revealed two destroyers of the “Narvik” Class, [28] an ex-Dutch destroyer [29] taken over by the Germans following the capitulation of the Netherlands, and one Elbing destroyer, the T-24 of the 4th German Torpedo Boat Flotilla which had eluded ships of the 10th Destroyer Flotilla on two previous occasions. The threat to the comparatively lightly armed anti-submarine groups on patrol duty in the Channel was considerable and it was expected that the German destroyers would shortly attempt to make their way to Cherbourg in order to disrupt Allied convoys carrying supplies to Normandy.

On the evening of 8 June, intermittent rain and low cloud over the Channel combined to produce weather conditions ideal for a sneak passage into the invasion area. Accordingly, Commander-in-Chief Plymouth at 1637 ordered all ships of the 10th Destroyer Flotilla to concentrate and take up the Western Patrol. [30] Later in the evening the group (now reconstituted as Force 26) was ordered to leave this area in order to take up a new patrol some fifteen miles off the Brittany coast between Ile de Bas and Ile Vierge. Force 26 was to be at the eastern end of the new patrol line by 2200. In the meantime, four anti-submarine groups sweeping in mid-Channel were temporarily withdrawn northwards.

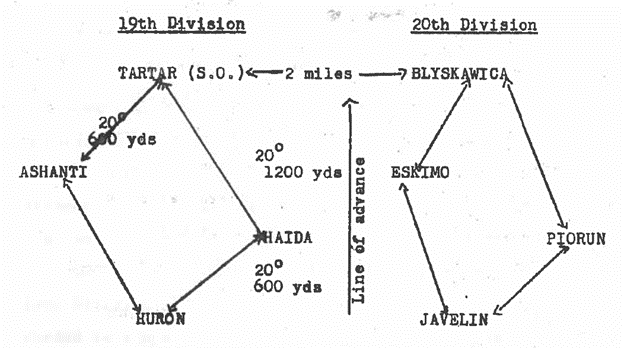

HMS Tartar, Senior Officer, ordered the Force to be in the first degree of readiness by 2130 and disposed his ships in the following formation:

In this manner, with the 20th Division stationed two miles to seaward and to starboard of the 19th Division, in order to broaden the front and increase the chances of intercepting the enemy, the 10th Destroyer Flotilla, swept southwards towards the French coast. The patrol area was reached on schedule and a zigzag sweep at twenty knots between Ile de Bas and Ile Vierge commenced. At 2236 Commander-in-Chief Plymouth ordered the patrol line shifted five miles northward because of the danger from enemy mine fields.

Shortly after 0100, proceeding westwards on the second lap of their Ile de Bas – Ile Vierge run, the Force picked up numerous “dubious” radar echoes. Low-lying clouds were interfering with radar transmissions and it was not until fourteen minutes later that one particular echo, bearing 251° at ten miles aroused the interest of the group. At 0120 Tartar ordered the zigzag to cease and speed increased to twenty-seven knots. In tense silence the ships closed the echo, now dead ahead and steering east. It was not long before four echoes were distinguished, steering 085° at twenty-six knots, distant six miles.

The range was now closing fast and at 0124 the enemy was heard to make a sighting report. Two minutes later the German ships carried out their familiar tactic of firing torpedoes while altering away in an attempt to escape at high speed. A minute later, at 0127, four enemy destroyers hauling off to port came into view at 4,000 yards. Combing torpedo tracks as they came, the 19th Division (Tartar, Ashanti, HAIDA and HURON) boldly closed to almost point-blank range. The Nazi leader, Z-32, escaped to the northwards while the remaining three destroyers altered round 180° to the west, hotly pursued by the 19th Division.

In the hope that the 20th Division, slightly astern and to starboard, would take care of Z-32, Tartar and Ashanti engaged the ex-Dutch destroyer, ZH-1, inflicting damage on her, while HAIDA and HURON opened fire against the Narvik Z-24 and the Elbing, T-24, scoring hits before the enemy made off to the southwest. Visibility, already limited by rain squalls, was further reduced by the heavy smoke which all ships were now making; friend and foe alike soon became hidden from one another. At 0138, the enemy leader, Z-32, having evaded the 20th Division, returned to the scene from the north and opened fire against Tartar, who suffered heavy damage to her radar and W/T gear as well as four killed and thirteen wounded. In the meantime, Ashanti continued to pound ZH-1, scoring many hits as well as two torpedo strikes. An hour later, the heavily-damaged enemy destroyer, her crew having abandoned her, blew up and sank.

HAIDA and HURON, frustrated in their attempt to bring Z-24 and T-24 to bay when they escaped to the south-westwards by crossing (with impunity) through a British mine field which the Allied destroyers were expressly forbidden to enter, gave up the chase at 0215 and altered back to join their group. While returning, HAIDA at 0223 obtained a firm radar contact at six miles, bearing 032° on her port bow. At first this was thought to be the crippled Tartar who had been estimated to bear 040°. Challenged by light, the mystery ship returned an unintelligible reply. By now the ships had closed to within a mile. All guns were brought to bear and the challenge was repeated. Still under the impression that this might be Tartarwith her signalling equipment and radar out of action, HAIDA and HURON passed astern of the destroyer. At once, the mystery ship altered away to the south, dropping a smoke float as she fled and leaving no doubt as to her identity. HAIDA and HURON gave chase. At 0255 the Tribals opened fire with star-shell which revealed, silhouetted in the glow, the Narvik flotilla leader Z-32. Fleeing southwards at thirty-one knots, the enemy began to open the range. His avenues of escape, however, were narrowing. The possibility of returning westwards to Brest was effectively blocked by HAIDA and HURON, to continue on a southerly course could only lead to his destruction on the rocks off Ile Vierge, only a course eastwards towards Cherbourg lay open to him, and to alter onto an easterly course he had to cross through an Allied mine field. At 0311, taking his chances on the mine field, the Nazi destroyer altered sharply to port.

HAIDA and HURON, checked by the same obstacle which had cost them their earlier pursuit of Z-24 and T-24, swung back northwards to skirt the barrier in an agony of suspense lest this destroyer also should elude them. At 0340 contact with the enemy was lost, the range having been opened to more than 18,000 yards. Although the chances of overhauling seemed slim indeed, the Tribals continued to sweep to the eastwards. Their tenacity was rewarded when, twenty minutes later, contact was regained, the enemy bearing 070° at 20,000 yards. HAIDA and HURON maintaining a speed of thirty-one knots, altered to 070° to parallel the enemy’s course, but the range could not be closed sufficiently to enable the destroyers to open fire. However, the Tribals held on grimly and then, unexpectedly, for some reason never established, the enemy swung round to starboard, steering a south-westerly course, possibly with the intention of slipping into Morlaix. It was the kind of move the Tribals had been hoping for. Closing in from the north, they narrowed the range to 7,000 yards when both ships opened fire with star-shell and main armament. Z-32 replied with very effective fire, his first salvo landing some fifty feet ahead of HAIDA. The Tribals obtained some hits on the enemy which appeared to cut his speed, while at 0448 the Narvik altered to the south, possibly in an effort to take avoiding action. This course took him through another mine field, which he again successfully crossed. Emerging from the mine field at 0500, Z-32 bore about 60° on HAIDA’s port bow, steering a course almost due south. The three ships were now bearing down upon the rocky shoals off the French coast at high speed. Repeated hits were made on the enemy until 0517 when the action came to a climatic end. Z-32 was forced ashore on the jagged rocks off Ile de Bas. In the pale light of the approaching dawn, clouds of dense black smoke could be seen rising from the beached destroyer. A final well-placed hit at 0525 started a large fire which lit up the area as HAIDA and HURON shaped a course to rejoin their group. Once more, as Force 26 passed through Plymouth gate at 0850, battle ensigns were proudly flying at the peak. At a stroke, one of the serious menaces to the safety of the invasion supply lines had been removed.

Following the successful action on 9 June, bolder tactics were adopted by the ships of the 10th Destroyer Flotilla. On the night of 12 June, HAIDA in company with HURON, sailed to carry out a diversionary sweep in the vicinity of the Channel Islands. [31] An Army Major and several signalmen together with a supply of military equipment were embarked in HAIDA for the purpose of passing “intelligence” messages which would lure the enemy into believing an Allied landing was to take place on the west coast of the Cherbourg peninsula. It was hoped that such a feint would draw off part of the heavy force defending the valuable seaport at Cherbourg and thus facilitate its capture by the armies of liberation. After midnight the Tribals moved in, steaming in line ahead, well within range of Nazi shore batteries. The mock landing was heralded by a heavy Allied air bombardment of the beaches and HAIDA’s men watched with considerable interest, and some anxiety, the massive fireworks display bursting above the fiercely contested peninsula. The men agreed it was not exactly their “cup of tea” and no one was any the sadder when at last the order was given to clear the area and shape course for the more familiar mid-Channel waters where a destroyer had some sea-room in the event of an encounter with enemy forces.

Throughout the latter part of June the destroyer was frequently called upon to carry out patrols in support of the anti-submarine groups which maintained a constant vigil in the Channel to assure that the vital “build-up” convoys in support of the invasion forces were not molested by U-boats. On the afternoon of 24 June, on just such a patrol, HAIDA added another proud laurel to the already impressive array of garlands that she was winning for herself.

Earlier in the day Commander-in-Chief Plymouth had ordered HAIDA, together with the British Tribal Eskimo, to patrol the area some thirty miles due south of Land’s End. The Royal Navy’s 2nd Escort Group, led by the famous U-boat killer, Captain F. J. Walker, was hunting a submarine in the vicinity north-west of Ushant, and upon her arrival HAIDA had received a signal from Captain Walker informing her that he was now searching some ten miles north-northwest of Ushant where an aircraft had recently sighted a U-boat on the surface. HAIDA reached the area at 1508. A cloudless blue sky, calm sea and exceptionally good A/S conditions in the Channel presented an ideal setting for a good afternoon’s hunting.

Half an hour after their arrival in the area, a Czech Liberator [32] was observed dropping depth-charges on a surfaced U-boat some five miles astern of the Tribals. This was U-971 who had been subjected to repeated attack from the air since departing her base at Kristiansand, Norway, two weeks earlier. Routed northwards past the British Isles, she was proceeding on her first operational cruise when she was recalled on 22 June to attack Allied shipping in the Cherbourg area. Having suffered considerable damage to her torpedo-tubes, U-971 was making for Brest when she was surprised on the surface by the Czech bomber who carried out an attack and then marked the spot where the U-boat had dived. HAIDA and Eskimo immediately turned and swept towards the smoke marker in line abreast. Speed was reduced to seven knots when two miles distant from the marker in order to facilitate the A/S search. The first attack was carried out at 1626. The submarine lay on the bottom, motionless, hoping to be mistaken for one of the multitude of wrecks which littered the Channel floor.

Two hours later, at 1825, the Tribals delivered their ninth and final attack. This started leaks which shortly had the submarine’s crew standing in six inches of water and the Commander decided to bring his badly shaken boat to the surface. The destroyers promptly opened fire with main armament and close-range weapons to forestall any attempt by the U-boat to escape on the surface. A salvo from HAIDA’s “B” gun scored direct hits on the conning tower destroying its base and starting a fire. With their submarine sinking beneath them, the Nazis took to the water. Between them, HAIDA and Eskimo succeeded in picking up fifty-three of the crew of fifty-four. The prisoners were landed at Falmouth at 0300 on the 25th and the destroyers then shaped course for Plymouth. HAIDA received hearty congratulations from many quarters; not the least of which was a message from the cruiser Black Prince who signalled: “Narviks, Elbings and submarines all seem to come alike.”

Following her latest success, HAIDA’s company enjoyed a short period of leave while their ship was dry docked at Devonport. Two weeks later HAIDA was back with the 10th Destroyer Flotilla whose operations were now being vigorously extended into the inshore waters of the Bay of Biscay.

On the night of 13/14 July, HAIDA, in company with HMS Tartar (S.O.) and the Polish destroyer Blyskawica, was detailed to carry out an offensive sweep off the approaches to Lorient, one of the important Biscay bases still in enemy hands. Moreover, the coast around Lorient was strongly defended by heavy gun batteries and radar stations; German air bases on the Breton Peninsula, while lacking some of the punch of the early days, were still in operation.

The first night’s sweep was uneventful, but the second night (14/15 July) brought the destroyer into contact with a group of three enemy vessels. A clear moonless night, with light airs and a calm sea, augured well for the success of the forthcoming engagement. The enemy was first detected at 0209, bearing 051° at thirteen miles, zigzagging on a southerly course. Tartar, Blyskawica and HAIDA, weaving eastwards in line ahead, reduced their speed to twenty-two knots in order to draw the convoy well clear of the inshore mine fields and shore batteries. At 0300 the enemy was illuminated and immediately engaged. Tartar took on one of the merchantmen, Blyskawica engaged the trawler (which was towing a large battle practice target) while HAIDA directed her fire at a large merchant vessel. The enemy sent back a brisk return of fire, well-directed but erratic. No damage was sustained by the destroyer force which cleared the area at high speed forty minutes later, having sunk one of the merchantmen and leaving the other two vessels heavily on fire and sinking. The B.P.T. was also smoking fiercely, having drawn several salvoes before its strange identity and harmless character were revealed.

Four more patrols off the French coast throughout the next two weeks brought no encounter with the enemy until the night of 5/6 August when HAIDA took part in one of a series known as “Operation Kinetic” [33] which ended with the destruction of an entire enemy convoy and its escort. Following the establishment of an Allied bridgehead in Normandy, it had become apparent that the enemy intended to hold on to the west coast ports along the Bay of Biscay as long as possible. La Rochelle, La Pallice, St. Nazaire, Lorient and Brest, although no longer effective U-boat bases, since the Nazis had begun withdrawing their submarines northwards to Norway, were still held by large German garrisons which denied the Allies the use of these ports and harassed naval operations in the area. Isolated by land, these garrisons continued to be slenderly fed by sea, and operation “Kinetic” was designed with the object of permanently breaking up their coastal supply links. Small merchant vessels, heavily protected by armed trawlers, converted minesweepers, and occasionally by destroyers, crawled up and down the coast in short moves by night, under cover of shore batteries and with the added protection that the mined and rocky shoal waters gave to them. Even discounting the danger of air attack from nearby air-fields, it was not a healthy place for Allied cruisers and destroyers.

Force 26, consisting of the British cruiser Bellona, (S.O.), the RN destroyers Tartar and Ashanti, and the Canadian Tribals HAIDA and IROQUOIS, was sweeping near Ile d’Yeu in the Bay of Biscay on the night of 5/6 August when radar echoes of an enemy convoy working slowly to seaward of Ile d’Yeu were picked up. The British force held their fire until the moment when they could cut in between the enemy and the land, and at 0034 the order was passed to move in and engage the enemy. The action was not broken off until two hours later, when the convoy and its escort, believed to have totalled eight or nine ships, had gone down to almost total destruction. Prisoners of war who were later picked up revealed that eight or nine hundred special troops who were being evacuated in the coasters had gone down with their ships.

While none of the Allied ships sustained any hits, an unfortunate accident in HAIDA, when a shell exploded upon entering the breech of the gun in “Y” turret, killed two of her gunners and wounded eight more. The damage to HAIDA, however, was not crippling, and when Force 26 regrouped to attack a second enemy convoy moving between Belle Isle and Quiberon Bay, HAIDA went in also. Unfortunately, the results of the second action were inconclusive although some damage was inflicted and the convoy forced to put back to port. With daylight approaching, Force 26 was ordered by Commander-in-Chief Plymouth to return to harbour.

Upon her return to port HAIDA was taken into dockyard hands for repairs which kept her out of further action until 22 August when she returned to offensive patrols in the Biscay area. On the ninth of August her two battle fatalities were buried at Weston Mills Cemetery, Devonport, with full naval honours.

On the morning of the 30th August HAIDA was detailed with her sister Tribal IROQUOIS to rendezvous with the French cruiser Jeanne D’Arc, bound from Algiers to Cherbourg with fifty members of the French Provisional Government who were returning to the recently liberated City of Paris. The cruiser, bound on her historic mission, was met on the morning of 31 August as she was entering the Bay of Biscay and, with the two Canadian Tribals formed up in line ahead, escorted to Cherbourg.

HAIDA’s last few weeks of operations before returning to Canada for refit were concerned not so much with attacks on Nazi destroyers and enemy shipping (which showed considerable reluctance to put to sea after the August success of the 10th Destroyer Flotilla) but in the establishment of liaison with the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) whose heroic resistance to the German invader played no small part in the ultimate liberation of France.

On the morning of 6 September HAIDA lay off Les Sable d’Olonne while the Royal Navy destroyer Kelvin carried out a patrol to seaward, the First Lieutenants of both ships having proceeded ashore earlier to meet with Maquis [34] representatives and size up the situation in the local area. Shortly after noon a signal from the FFI warned the destroyers that two armed German Vedettes [35] were approaching from the northwards, three miles away. Kelvin shaped course at once to intercept and when HAIDA joined her at 1320 both vessels, bearing a large number of army and navy personnel attempting to escape from Brest to La Rochelle, had been captured. The boats were taken in tow, but HAIDA’s, which had been damaged in the brief exchange of gun-fire, sank before it could be brought into Les Sables. The other, which contained a number of secret documents, valuable radio equipment and weapons, was turned over to the FFI who were sorely in need of arms and equipment.

HAIDA’s operations in the now-familiar waters of England’s “narrow seas” were drawing to a close. Upon her return to Plymouth she embarked stores and equipment prior to sailing to Canada for refit. After a farewell visit from the Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, HAIDA, on the evening of 22 September, weighed anchor and glided down harbour amid the resounding cheers of those who watched her off. With some sadness, her men watched as Eddystone Light and the low-lying hills of Devon faded into the dusk, but spirits quickened again when the swift-moving destroyer, swinging out into the vast Atlantic, headed for home.

HAIDA arrived at Halifax on the morning of 29 September. A thin drizzle cloaked the harbour in a grey mist as the ship glided in past the gate vessels and anxious eyes sought out the old familiar landmarks. Unexpectedly, from a tug circling in the wake of the destroyer, a navy brass band struck up “Hearts of Oak” and hundreds of whistles from the ships in harbour burst forth in such a welcome as the old port had rarely seen. Ships’ companies from the destroyers, frigates and corvettes tied alongside the naval jetties lined the rails to add their cheers to the resounding cacophony of the celebration.

Three months later, HAIDA, sleek and trim after her refit, was racing back across the North Atlantic to join the Home Fleet for a series of operations off the coast of Norway and on the Murmansk route to Russia. Commanded by Acting Lieutenant-Commander R.P. Welland, RCN, the destroyer arrived at Plymouth on the evening of 11 January, 1945, where she was taken into dockyard hands for the installation of new types of radar equipment. Upon the satisfactory completion of radar trials, 24 February, HAIDA sailed independently for Scapa where she commenced working-up exercises under the supervision of Commodore (D) Home Fleet.

On the morning of 19 March, HAIDA sailed from Scapa as part of Force One [36] to take part in operation “Cupola”, a mine-laying strike in the narrow waters off Granesund on the coast of Norway. While the aircraft laid their mines in the southern entrance to Askevold Anchorage, HAIDA provided A/S screen for the striking force, standing out to sea beyond the mine barrier set up by the enemy. HAIDA also acted as plane guard during flying operations. “Cupola” was carried without hitch, and the entire Force returned to Scapa on the afternoon of 21 March.

Three days later, HAIDA, as part of Force Two, [37] departed Scapa for an anti-shipping strike by carrier aircraft along the Norwegian coast. The operation [38] was planned as an air strike against shipping in the Trondheim Fiord leads, but, not finding any worth-while targets on the morning of 26 March, the bomb-carrying Avengers attacked radar and radio installations. On the morning of the 28th a second strike was flown off against several enemy merchant ships, two of them being set on fire. Although the surface forces saw no action, three ME. 109’s were destroyed in combat and one Barracuda aircraft from Puncher was lost.

HAIDA’s next and last war-time operation, [39] before the unconditional surrender of Germany on 8 May brought the fighting in Europe to an end, took her back to the bleak convoy route to Russia where eighteen months earlier the eager young Tribal had first fired her guns in anger. The war at sea, and especially in the frigid waters off the roof of Europe, had lost few of its dangers, none of its challenges. The German surface fleet had been sunk or stilled, but the Nazi undersea fleet still posed a threat which was not to be discounted until the long-awaited hour of armistice brought an end to the bitter battle which was the war at sea.

HAIDA’s activities in operation “Roundel” absorbed her last four weeks before the close of the war with Germany. On 7 April the destroyer sailed independently to Greenock where she was to provide escort for seven Russian submarine chasers on passage to Murmansk. After a bout of particularly foul weather which force the ships to seek shelter first in Loch Ewe and later, encountering heavy gales off the Orkneys, to put back into Thurso, HAIDA shepherded her charges into Skaalefiord in the Faeroes on 15 April where they were to rendezvous with Convoy JW-66. Junction was made at noon on the 19th and the convoy (twenty-seven merchantmen and sixteen submarine chasers) proceeded northwards under the protection of a heavy Allied escorting force. [40]

Enemy submarines and aircraft kept their distance from the powerfully escorted convoy, the only excitement being provided on 22 April by a Swordfish aircraft from Vindex which crashed on taking off. The pilot and observer were quickly recovered unhurt by HAIDA and returned to their ship the following morning. On the afternoon of the 25th elaborate preparations were made by the convoy escort to assure the safe passage of the cargo ships [41] through the danger area off Kola Inlet. Some three hundred “scare” depth-charges were dropped while HAIDA and IROQUOIS covered the flanks of the convoy with smoke laid at high speed. At midnight the merchant ships and their escorts were all riding at safe anchor in the quiet harbour of Vaenga Bay.

Here, surrounded by desolate, snow-covered hills, HAIDA waited throughout the next four days for the return convoy RA-66 to form up for the passage to Britain. Hours before the ships sailed on the night of 29 April, frigates of the 19th Escort Group, sweeping in the approaches to Kola, destroyed two U-boats. [42] During the hunt one of the Group’s frigates, HMS Goodall, was fatally torpedoed and sank with heavy loss of life. The convoy, strongly protected, ran the gauntlet of the enemy’s Arctic U-boat force without damage, although HAIDA and IROQUOIS both reported “near misses” by torpedoes.

The merchant ships arrived safely at the Clyde, despite enemy aircraft, submarines and snow storms, on 8 May 1945. HAIDA, with the Home Fleet section of the escort had detached for Scapa on the 6th, and here, two days later, her ship’s company celebrated the Allied victory in Europe.

The following week was spent cleaning and painting ship in preparation for HAIDA’s forthcoming cruise to “show the flag” to some of the liberated peoples of Europe. On the morning of 16 May, Canada’s Tribals HAIDA and HURON proceeded in company with HM Cruiser Berwick for operation “Kingdom”, the first official peace-time visit to Trondheim, Norway. The ships arrived off Grip Island on the following morning and proceeded up the Trondheim Lieden where they were met, ironically, by a German “M” Class minesweeper which transferred a pilot – a German naval officer – to Berwick for passage up the fiord. Many small boats, filled with enthusiastic Norwegians, came out to greet the ships. Wide-eyed youngsters and gaunt, sombre-faced adults were welcomed aboard the destroyer and treated to tempting varieties of food. Everywhere, a festive mood prevailed and grim memories of war faded, if only for a time, from the faces of those who had lived close to its horrors for five long years.

HAIDA returned to Scapa late on the night of 24 May. A triumphant tour had climaxed a successful career and now the ship was preparing to return to Canada where plans were in progress to sail her for duty in the Pacific theatre. On the 25th, HAIDA and HURON in company departed Scapa for Greenock where they were shortly joined by IROQUOIS. On the 4th of June, the three battle-tested Tribals, pride of the Canadian fleet, slipped and proceeded down channel, west-bound for home.

At 0900 on the morning of 10 June 1945, HAIDA, HURON and IROQUOIS arrived home. Halifax accorded them a rousing welcome, highlighted by a personal message from the Chief of Naval Staff, Vice-Admiral G. C. Jones, CB, RCN, who was on hand to greet the returning Tribals.

The destroyers were at once taken in hand for refit and tropicalization in accordance with plans already in motion to sail the ships with all dispatch to the Far Eastern theatre. When the unconditional surrender of the Japanese forces on 14 August 1945 brought the war in the Pacific to an end, HAIDA, with many another of Canada’s fighting ships, passed into reserve.

A year and a half later, on 1 February 1947, HAIDA emerged from her period of inactivity. Faded now were the war-time glories, the fame, the fighting trim. To the men who now commissioned her, HAIDA must have appeared an unlovely, littered, rusted, dead thing. Much time and effort were required to restore the veteran destroyer to the days of her prime. At first, nothing went well. Her work-ups were dogged with ill luck although the younger men aboard her doubtless considered the mishaps more in the nature of temperamental outbursts than the product of fate. Her wheel-house caught fire. A boiler burst. Each time she had to be brought back into dockyard hands for further repairs.

HAIDA, once the darling of the fleet, seemed, observed one officer at Headquarters, in danger of developing a “Cinderella complex”. Such is the strange fortunes of ships-of-war in the tranquil days of the peace which their efforts have helped to produce.

Slowly, throughout the summer and autumn of 1947, life aboard the destroyer began to shake down into normal peace-time routine. Exercises and training cruises in North American waters absorbed her sea time until February 1948 when HAIDA was taken in hand for her annual refit.

Upon completion of her refit in mid-April, HAIDA engaged in a busy round of activity during the summer of 1948 which brought the destroyer to almost war-time tempo. Inevitably, a ship’s spirit was kindled and the legend that was HAIDA began to live again. While operating with HMCS MAGNIFICENT as plane guard in August, HAIDA had a chance to exhibit the high level of efficiency which now prevailed. On two occasions, airmen who had ditched were recovered in record time by HAIDA’s sea-boat. One rescue was accomplished in a cool two minutes – a commendable example of the training and team-work which was now beginning to pay dividends.

The following month, September 1948, HAIDA accompanied MAGNIFICENT and NOOTKA on a cruise into northern waters which took her up the Labrador coast, along Hudson Strait and down to Churchill in Hudson Bay. This was the first time major warships of the RCN had engaged in operations in Canada’s Arctic waters.

A year later, HAIDA took part in the American amphibious landing exercise (“Noramex”) which took place during the latter part of October off Cape Porcupine, Labrador. The Canadian destroyer formed part of the advance fire support unit which carried out a bombardment of the beaches before the landing ships moved in. The exercise successfully completed, HAIDA returned to Halifax 27 October.

Three weeks later, while at sea with MAGNIFICENT and SWANSEA, HAIDA’s sea-boat crew once again had an opportunity to prove themselves, this time against some stiff competition. On the afternoon of 17 November 1949, orders were received by the group to proceed with all dispatch to an area some 400 miles north-west of Bermuda where a missing American B-29 aircraft had disappeared. The story of the subsequent rescue of the airmen is graphically told by HAIDA’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Commander E. T. G. Madgwick:

“The group reached the assigned area by 0800 18th November, and aircraft were flown off. The search was not completed however when fresh instructions were received for the group to proceed to a new area about 300 miles to the North East of Bermuda in the vicinity of 36°. 07’N. 60° 30’W. where flares had been sighted. All aircraft were flown on by 1201, and course altered to 088°, with speed 18 knots. The wind which had eased during the previous night began to get up again about 2000, blowing from the west force 4. SWANSEA was detached to proceed independently to the area during the afternoon.”

“At 0620 on Saturday 19th November, SWANSEA was overtaken. At this time MAGNIFICENT and HAIDA were still doing 19 knots, but the wind having increased to force 6, a heavy sea was running from the N.W., causing the ship to yaw considerably.”

“At 1020 HAIDA investigated a radar contact which turned out to be U.S.S. Barataria, a coast guard seaplane tender. Aircraft were also sighted at various times during the forenoon. At 1203, when the task group was 40 miles away from the estimated position of the survivors, aircraft were flown off to search. A heavy sea was running and MAGNIFICENT was an inspiring sight as she rolled and lurched. There was frequently a horrid moment when the aircraft taking off dipped from view below the rising bow. HAIDA too, on one occasion rolled to 42°.”

“At 1330, MAGNIFICENT commenced to fly on aircraft, and it was at this stage that the seas were observed to break over her bow and came rolling down the Flight Deck, while aircraft were attempting to land. However, by 1410, all aircraft were on board except one, who appeared to be late returning. While waiting for this late arrival, a B-17 was observed to the south, and when it was noticed that it was orbiting, the fact was reported to MAGNIFICENT.”

“At 1420, the B-17 was observed to drop a parachute. This fact which caused considerable interest in HAIDA, was also reported but no more could be done until the last Firefly had been landed on. The plane turned up at 1435 and started orbiting, and at the same time an object was observed to the northward which was soon identified as a U.S. Destroyer heading straight towards us and the B-17 beyond. Everybody was now convinced that the survivors were at hand, and it was therefore with considerable anguish that we watched the Firefly orbit 5 times before finally landing. Any compassionate thoughts regarding the difficult job the pilot had to do was swamped by the fact that every minute we could see the U.S. Destroyer getting nearer.”

“As soon as the Firefly was on, HAIDA was despatched to the Southward. Even now we had to spend a few minutes to get the seaboat turned in again before speed could be increased to 20 knots. I had not intended to exceed this as we were steering beam on to the sea, but the plot reported that the range of the U.S. Destroyer was down to 6½ miles and still closing, so we increased to 22, then to 24, and finally 26½ knots. The behaviour of the ship at this stage was most exhilarating, but in spite of the quantities of water which came on board, no damage was done except for on bent stanchion forward. Without any doubt, the Tribal Class Destroyer is a very fine seaboat, although a trifle wet.”

“At 26½ knots, we slowly drew ahead, and finally, with our rival 7½ miles away, a smoke float was sighted at 1526, to be followed immediately by 2 small empty floats, and a larger canvas boat with men in them.”

“Hitherto, I had not made up my mind whether to use a boat or not. However, having seen the flimsy nature of the float, and the wind having started to drop, reducing the number of breaking seas, we made what passed for a lee, and lowered the whaler (1532) which proceeded to the raft.”

“At this moment the rapidly approaching American started to call us by light. My first thoughts were that he wanted to claim the survivors for himself, and so to avoid any disconcerting signals, we did not answer until all the survivors were on board. It subsequently turned out that all he wanted to know was how many survivors were on board.”

“Meanwhile, the boat having reached the raft (1539), two of her crew got in with the survivors as the latter were unable to tend any lines. As it was now obvious that the whaler could not pull back to the ship, the ship was brought alongside the whaler, on the other side of which was secured the raft. The latter was then secured abreast of the starboard quarter where a scrambling net was rigged. With two men on either side of the net, the embarking of the survivors was mainly a matter of waiting for the right moment. In some cases they practically stepped on board. By 1550, all survivors were on board, and having hoisted the whaler, the ship proceeded to rejoin MAGNIFICENT.…”

HAIDA’s rescue of the airmen brought many letters of congratulation to the ship and fresh honours to the ship’s company, who were shortly afterwards presented with a certificate proclaiming that:

“Whereas it has been brought to the attention of the nominating committee that the Officers and Crew of the Destroyer HAIDA have been outstanding in their field for many years and rescued the shipwrecked crew of a B-29 plane where Co-pilot was a Texan and whereas they would likely bring further honors to the State of Texas, they are hereby made Honorary Texans.”

At 1630 on 13 December 1949, HAIDA moved into her berth at Jetty 4, Halifax, completing the last engine movement of her second commission. During the next two years HAIDA remained in reserve, undergoing her conversion to A/S weapons [43] during which time squid mountings were fitted on her quarter-deck.

At 0900 on Saturday, 15 March 1952, colours and the commissioning pendant were hoisted in HAIDA, who thus became the first Canadian ship-of-war to commission under the sovereignty of a Queen. Her new Commanding Officer was Commander Dunn Lantier, RCN, who had been an officer aboard the old ATHABASKAN back in the days when she and HAIDA had been sister ships in the English Channel. One of the ones HAIDA had not been able to rescue at the time of ATHABASKAN’s sinking, Commander Lantier had spent the final twelve months of the war a prisoner in Germany. Fittingly enough, his first operation in the familiar Tribal took him back to the port at Plymouth, where HAIDA in the tense days of 1944 had found a safe harbour from the perils of war.

Detailed to act as plane guard for the carrier MAGNIFICENT during her crossing to the United Kingdom, HAIDA had sailed from Halifax on 2 June and arrived at Plymouth on the morning of 10 June 1952 – exactly eight years and a day since the night of her dramatic encounter with the Nazi destroyer Z-32 in the French coastal waters of the English Channel. During her stay at Plymouth, a copy of HAIDA’s ship’s badge [44] was presented to the City of Plymouth, in remembrance of the war-time bonds between the ship and the port and the spirit of goodwill which still prevailed.

HAIDA returned to Halifax on 26 June where the ship was stored and made ready for her departure to the Far East. After a farewell visit from the Chief of Naval Staff accompanied by the Flag Officer Atlantic Coast, HAIDA departed for Korean waters 27 September 1952. Passage through the Panama Canal was made on 3 October and two days later HAIDA, for the first time in her career, steamed out into the Pacific Ocean, bound for the Commonwealth naval base at Sasebo, Japan. Here she arrived on 12 November, having stopped over at Pearl Harbor for exercises, and the following week she sailed to join United Nations ships operating on the west coast of Korea.

While the war in Korea had been dragging on for almost two and a half years, the final armistice agreement was still a bitter eight months away. True, the hard fought see-saw operations in which spectacular advances were followed by staggering withdrawals, as first the Communists, then the United Nation forces, parried for position in the nightmare struggle of advance and retreat, belonged to the past. By July 1951, when the peace talks first began at Kaesong, the major battles had been fought, the heaviest casualties suffered, the majority of the incredible number of prisoners taken. Entrenched along the 38th parallel, the armies faced each other across the “no man’s land” of the buffer zone, each side ruthlessly defending his position, cautiously probing for weak spots in the other’s defences.

From July 1951, until the armistice was signed on the 27th of July 1953, the military situation generally remained static. The bored reflection, “war is mainly waiting”, was never more truly borne out than by these two years on the battle-ground of Korea as the armies dug in to hold and survive while the seemingly endless “peace talks” dragged on in the tents at Panmunjom. Savage outbursts of local activity flared up from time to time as a rugged hill-side or a barren ridge became the object of dispute; and men died, or were taken prisoner, or endured, as through two long years the “waiting war” went on.

For the United Nations naval forces, the war was settling into a routine of vigilance and blockade. The heavy naval bombardment in support of the UN forces backed up at Pusan, the daring and spectacular amphibious landings at Inchon, the assault at Wonsan, all belonged to the action-filled first year of the war in Korea; each had taken its place beside the great “combined operations” of history.

After 1951 the Canadian destroyers in the Far East were committed to the task of maintaining the UN’s “iron ring” about Korea for, primarily, the naval task was a blockading one. Local operations involved breaking up the enemy’s coast-wise traffic, the defence of the friendly west coast islands, and the bombardment of rail installations which skirted the foot of the cliff-bound east coast. Not a small part of the duty of RCN destroyers was the screening of aircraft carriers for the telling strikes which were made against enemy troop concentrations, supply dumps, bridges and other vital installations. The monotonous task of screening duty, however, was frequently enlivened by orders to proceed close inshore to bombard enemy shore positions or to assist guerilla forces in landings along the coast or on outlying islands in order to gather intelligence and take prisoners.

December found the destroyer on station off the east coast of Korea where her guns, for the first time, had an opportunity to engage the enemy. On the morning of 6 December having closed the island of Yong Do where supplies for the South Korean garrison stationed there were landed, HAIDA joined the USS Moore as gun-fire support ship to carry out a bombardment of factory and marshalling yards at Songjin. Hits were observed in the target area and when turning away, the enemy’s 76mm. shore batteries opened fire. HAIDA’s 3” 50 after mount rapidly scored hits which silenced the enemy position while the destroyers cleared the area with impunity.

During the next two weeks, HAIDA received her initiation into the Korean “Train Busters Club”, becoming the second RCN ship to earn her membership. [45] Shooting up Communist trains on the peninsula’s east coast was a tricky manoeuvre calling for a nice combination of navigational skill, gunnery control, and judgment. The trains travelled mainly under cover of darkness, hiding out by day in cunningly camouflaged tunnels. It was not a simple task to destroy these important supply trains during their flashes across the exposed stretches of track which brought them down to the water’s edge within reach of United Nations naval guns.

HAIDA had her first crack at one of these elusive targets on the night of 7/8 December with, what her Commanding Officer morosely described as, “nil results”. Things perked up a little when, ten days later, in the early hours of 18 December, HAIDA received a report that a south-bound train was heading towards her patrol area. The destroyer’s guns were ready and as the train flashed into view HAIDA opened fire at 4,000 yards. This time, although hits were scored, the train again managed to escape into the darkness. The following night, making full use of the experience gained in her previous box car duels, HAIDA bagged her first train. She had been at action stations for two hours when, at 0259, a north-bound train was sighted. Fire was immediately opened with 4-inch, 3-inch and star-shell. While the engine ground to a halt, HAIDA’s guns poured fire into the box cars, causing heavy damage. Stopping from time to time to allow the smoke to clear and survey the wreckage, HAIDA continued her bombardment until 0516 when she left the area to continue her patrol to the northwards.

Patrol followed patrol, highlighted only occasionally by the bombardment of an enemy gun emplacement or the sinking of a Communist mine. This was a different kind of fight from the one HAIDA had made her name at in the English Channel, but certain prerequisites remained the same: the need for constant vigilance, peak efficiency, team-work, and the aggressiveness which is the will to win – these went unaltered.

In June 1953, one month before the final armistice arrangements brought the war in Korea to a close, HAIDA’s first tour of duty in the Far East came to an end. Returning home via the Suez Canal and the sparkling Mediterranean, the ship completed her first circumnavigation of the globe when she steamed into Halifax, 22 July, to be met by Rear-Admiral R. E. S. Bidwell, RCN, who flew his flag in HAIDA as she entered harbour.

After a refit which lasted until late autumn, HAIDA departed Halifax, 14 December 1953, in high winds and snow flurries, bound for her second tour of duty in Korean waters. After an uneventful passage, she secured at Sasebo 5 February and the following week sailed for patrol duty on the west coast of Korea.

The armistice agreement, signed on 27 July 1953, [46] brought a formal end to the fighting in Korea, but the long vigil of the “uneasy truce” was just beginning. HAIDA, on her second “tour of ops”, carried out peaceful patrols in Korean waters with a view to ensuring that the conditions of the armistice were adhered to, since, for the next year and a half, the volatile prisoner-of-war question remained an explosive issue which continued to threaten the delicate balance of international relations in the Far East.

At dawn on 12 September 1954, HAIDA departed Sasebo one day ahead of schedule in an effort to avoid the fury of typhoon “June”, forecast to hit the area the following morning. The passage home, when HAIDA for the second time steamed round the globe, was highlighted on 23 September by “crossing the line ceremonies” which were enthusiastically carried out by her crew when the destroyer, on approaching the entrance to the Strait of Malacca, dipped down to cross the equator at 106° 14’ East, between the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. HAIDA arrived home on the first of November, bringing with her as mementos of the Orient some fifteen thousand dollars worth of personal souvenirs – among them, almost nineteen hundred feet of toy railroad track together with its accompanying “rolling stock”.

The following spring, after a winter in refit at Halifax, HAIDA embarked on a busy round of activities which took her, as part of Task Group 301.1 (MAGNIFICANT, MICMAC and HAIDA) down to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Bermuda, and to Portsmouth, England. In July, the destroyer sailed on a training cruise with UNTD cadets and gunnery rates to Bar Harbour, Maine. Next month, on the eight of August, HAIDA was allocated to the newly formed First Canadian Destroyer Squadron. With this group, HAIDA took part in September 1955 in the large-scale NATO exercise, “Sea Enterprise”.

Eight Canadian warships, organized into Task Force 301, [47] took part in these tactical manoeuvres off the Norwegian coast with ships from Norway, the United States and the United Kingdom. Exercising with other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization has, since its inception in April 1949, become an important phase of the training commitments for RCN ships and HAIDA’s activities were bringing her increasingly into contact with the navies of those nations whose interests and ideals are allied to the principles of NATO – that “great adventure” in the delicate and challenging field of international relations.

Throughout the fall cruise with CTG 301.1 the officers and men of HMCS HAIDA received an enthusiastic reception from the people of all ports visited, particularly Amsterdam, where “…the Canada Badge was…the entree into hearts and homes….” The official functions for officers and the numerous entertainments for the men provided at Amsterdam required a four-page appendix to the October Report of Proceedings.

On the way to Gibraltar HAIDA detached from CTG 301.1, and at 0112A 30 October stopped engines in the position of the sinking of the first ATHABASKAN, north of Ile de Bas, where a one minute’s silence was observed for the 128 officers and men lost on 29 April, 1944. It was singularly appropriate that ATHABASKAN’s sister ship on that memorable day should have carried out this observance. Following a month’s cruise in Mediterranean waters, the Task Group shaped course for Halifax, and on arrival HAIDA joined the First Canadian Escort Squadron (CANCORTRON ONE), the First Canadian Destroyer Squadron having been dissolved.

In the spring of 1956 HAIDA sailed to the Caribbean with CTF 301 [48] for a five-weeks’ programme of “work-ups” and A/S exercises, including Exercise “New Broom V”. On 22 May HAIDA again slipped from HMC Dockyard, Halifax, this time destined for a month’s cruise in the St. Lawrence River; she wore the board pennant of Commodore E. P. Tisdall, CD, RCN. At Montreal HAIDA, ALGONQUIN and IROQUOIS were visited by the Chief of the Naval Staff, Vice-Admiral H. G. DeWolf, CBE, DSO, DSC, CD, RCN, who met the officers of the Task Group on HAIDA’s after gun-deck. HAIDA then sailed for Sorel, and later for Port Alfred on the Saguenay River, where the Commander “…was distressed to find that few people had heard of either the old or new SAGUENAY, and received news of the new ship with great delight.” Thence HAIDA proceeded to Gaspe, where the citizens entertained enthusiastically and the Isaak Waltons among the ship’s company “…were once again in their piscatorial heaven.” While the River cruise had proved to be one of the most enjoyable in HAIDA’s eventful history, it had definite, long-term advantages in producing a greater familiarity with home waters and acquainting the smaller ports with the role of the Royal Canadian Navy.

In September HAIDA sailed in company with MAGNIFICENT, ALGONQUIN, HURON, IROQUOIS and ST. LAURENT to participate in the NATO exercise “New Broom VI”. Hurricane Carla upset the exercise schedule with force 8 winds on the 9th and 10th, and HAIDA was detailed to escort ALGONQUIN, whose topmast had buckled, part way back to Halifax. She rejoined the group after completing this duty, remaining with MAGNIFICENT, IROQUOIS and HURON on the Support Group Screen until the completion of exercises on 15 September.

While carrying out refit trials on 18 March, 1957, HAIDA received notice to assist in the search for an overdue Avenger aircraft from SHEARWATER, being joined in the Halifax approaches by LAUZON, PORTAGE and GRANBY. On taking station LAUZON and PORTAGE collided, causing considerable damage to the latter’s forepeak. HAIDA and GRANBY escorted both vessels back to port and resumed the search, which was abandoned two days later.