HMCS RAINBOW. Photo Catalogue No. VR991.370.2.

When the First World War was declared on 4 August, 1914, HMCS RAINBOW was already steaming south towards Mexico with orders to seek — and preferably destroy — a pair of armed and aggressive German cruisers.

The cruisers Leipzig and Nuremberg were prowling the Pacific, and two sloops operating in southern waters, HM Ships Shearwater and Algerine, were considered vulnerable to attack. It was also feared that the Leipzig would bombard the coast.

HMCS RAINBOW gun crew. Photo Catalogue No. VR993.152.4.

Despite her lack of guns and armour, RAINBOW was expected to outface the heavier ships and big guns of the enemy’s Far Eastern Squadron and escort the vulnerable British vessels safe back to their base at Esquimalt. In the end RAINBOW, never met the German threat. But she acquitted herself well on the mission, capturing two German-owned schooners, Leonor and Oregon.

Throughout the war, RAINBOW continued patrolling the coast, sometimes as far as Panama, seeking German warships and shipping. She scouted BC coastal waters to ensure no German auxiliaries such as coal supply vessels were hiding or spying on ship movements. It was a huge task; she was the only allied warship protecting the entire west coast of North America. But it was also a glorious period in her career with the fledgling Canadian navy.

RAINBOW was commissioned at Portsmouth on 4 August, 1910, but did not legally become an RCN vessel until her arrival in Esquimalt. She was one of two old cruisers bought from the British Admiralty by Canada’s Dominion Government. The other vessel was the armoured cruiser NIOBE. The Royal Canadian Navy had just been established, and to operate a navy, Canada desperately needed ships, and personnel. RAINBOW, with a complement of three hundred officers and men under Commander J.D.D. Stewart, R.N., sailed to her new home in Esquimalt via the Straits of Magellan, arriving on 7 November, 1910.

RAINBOW arrives in Esquimalt harbour on November 7, 1910. Photo Catalogue No. VR991.370.6.

For several months after her arrival, RAINBOW moved up and down the west coast recruiting, training and showing the flag, but she was forced into comparative inactivity by the slow build up of the RCN. In 1911, Commander Walter Hose, who had been trained in the Royal Navy, was loaned to Canada by the Admiralty to become RAINBOW’s captain. He was the first officer of the Royal Canadian Navy to be appointed to this position and RAINBOW was the first Canadian Man-of-War to fly the Senior Naval Officer’s Pendant.

For many months, RAINBOW lay idle in Esquimalt, mainly due to a lack of crew members (many of the original crew did not renew their contracts). There was also a lack of the political will and financial backing needed from Ottawa to build up Canada’s naval strength.

In July 1913, a group of Victoria citizens organized a naval volunteer detachment, which marked the beginning of the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve. Several officers and men from RAINBOW helped this first unpaid and unofficial detachment by giving instruction and encouragement, with the approval of their Commanding Officer. Walter Hose is credited with being the Father of the Canadian Navy for his foresight in spending the limited funds available to him on building and maintaining a strong reserve force.

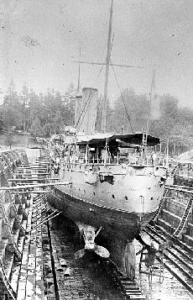

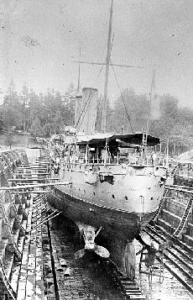

HMCS RAINBOW in Esquimalt graving dock. Photo Catalogue No. VR992.19.7.

The formation of the detachment of naval volunteers was not achieved without difficulties. Although it was authorized by an Order-in-Council passed in July 1914, the Canadian Government did not implement the formation of a volunteer reserve until after the beginning of the First World War.

That same year, RAINBOW was sent to Vancouver to deal with with the arrival of the Komagata Maru, a ship whose passengers, Sikh immigrants from India, were testing Canada’s laws designed to block immigration from South Asia. The passengers weren’t allowed to disembark, even though they had as much entitlement, being British subjects, as the RAINBOW crew members sent to repel them. Rainbow eventually succeeded in forcing Komagata Maru to go back to India; some of Komagata Maru‘s passengers were killed, upon their return there.

A monument in memory of the Komagata Maru incident is located near the steps of the seawall that leads up to the Vancouver Convention Centre in Coal Harbour.

In 1917, as the war against the German U-boats in the Atlantic reached a critical point, anti-submarine vessels were collected from all sources to patrol the Atlantic seaboard. Because every trained officer and man was needed to man these vessels, the Canadian Government and the Admiralty agreed to pay off RAINBOW on 8 May, 1917, and transfer her crew to the east coast.

In June, she was re-commissioned in Esquimalt as a depot ship and finally, in 1920, RAINBOW was sold to a Seattle firm for scrap.

by Clare Sharpe

Museum staff member/webmaster

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum